Wilderness Risk Management Conference

Portland, ME, 2025

This is not intended to be self-explanatory. I've tried to add some context for folks who weren't in attendance.

Comments and questions are welcome. A few people came up to tell me some of their decision-making stories, and they were awesome.

You can message me through the Contact link in the menu bar at the top of this page.

Intro: I told a story about last week's ridiculous dream wanting to paddle a river at a high-for-me water level, and explaining to my partners that "for this to work, you'd need to enjoy spending the day holding my hand and helping me get down the river." They decided to go without me, and I was totally okay with that.

Part 1: Getting on the same page with terminology, welcome to my brainspace.

Part 2: Examples

"Care" instead of "awareness" because care implies a willingness to do work ... make effort.

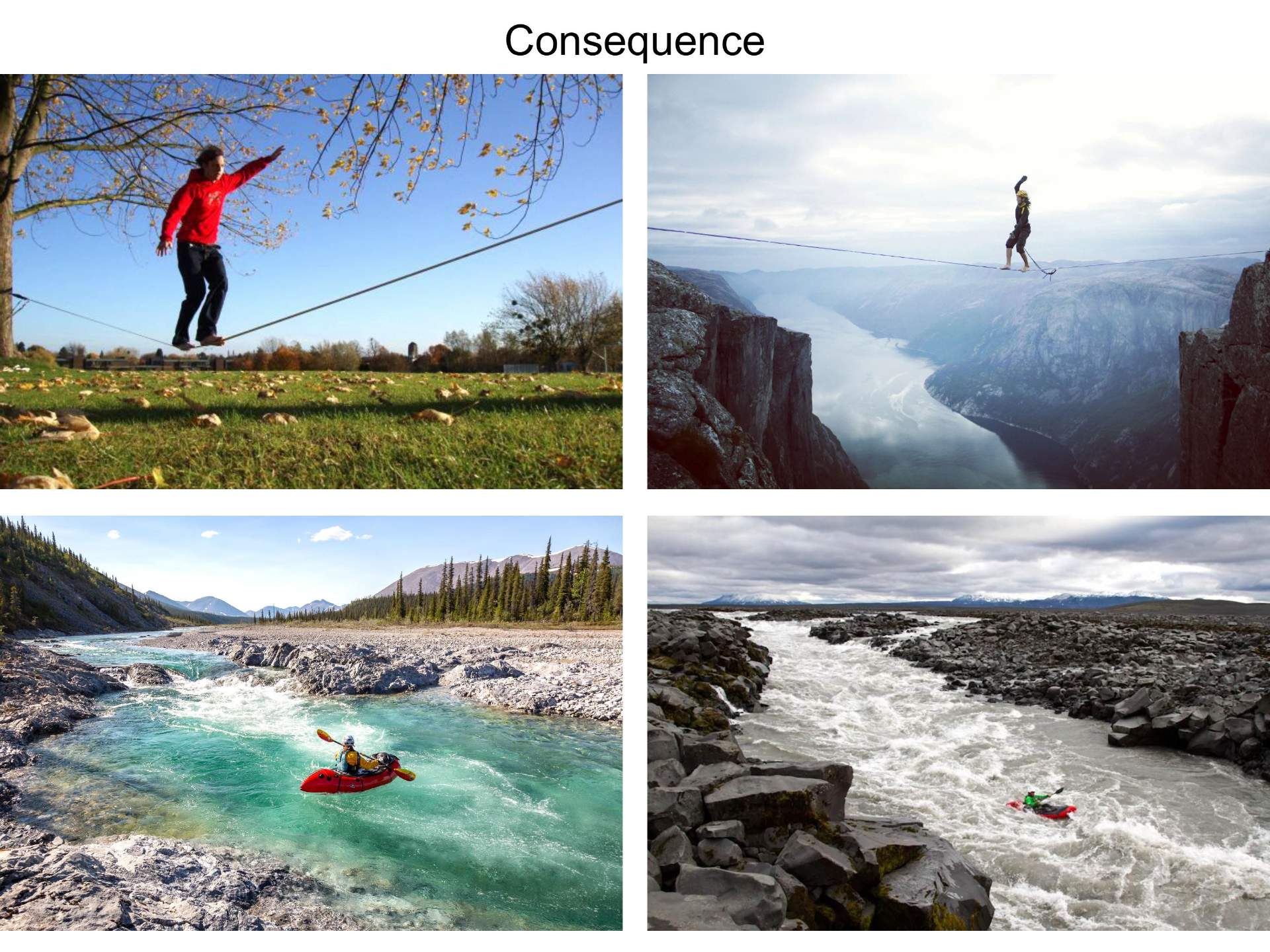

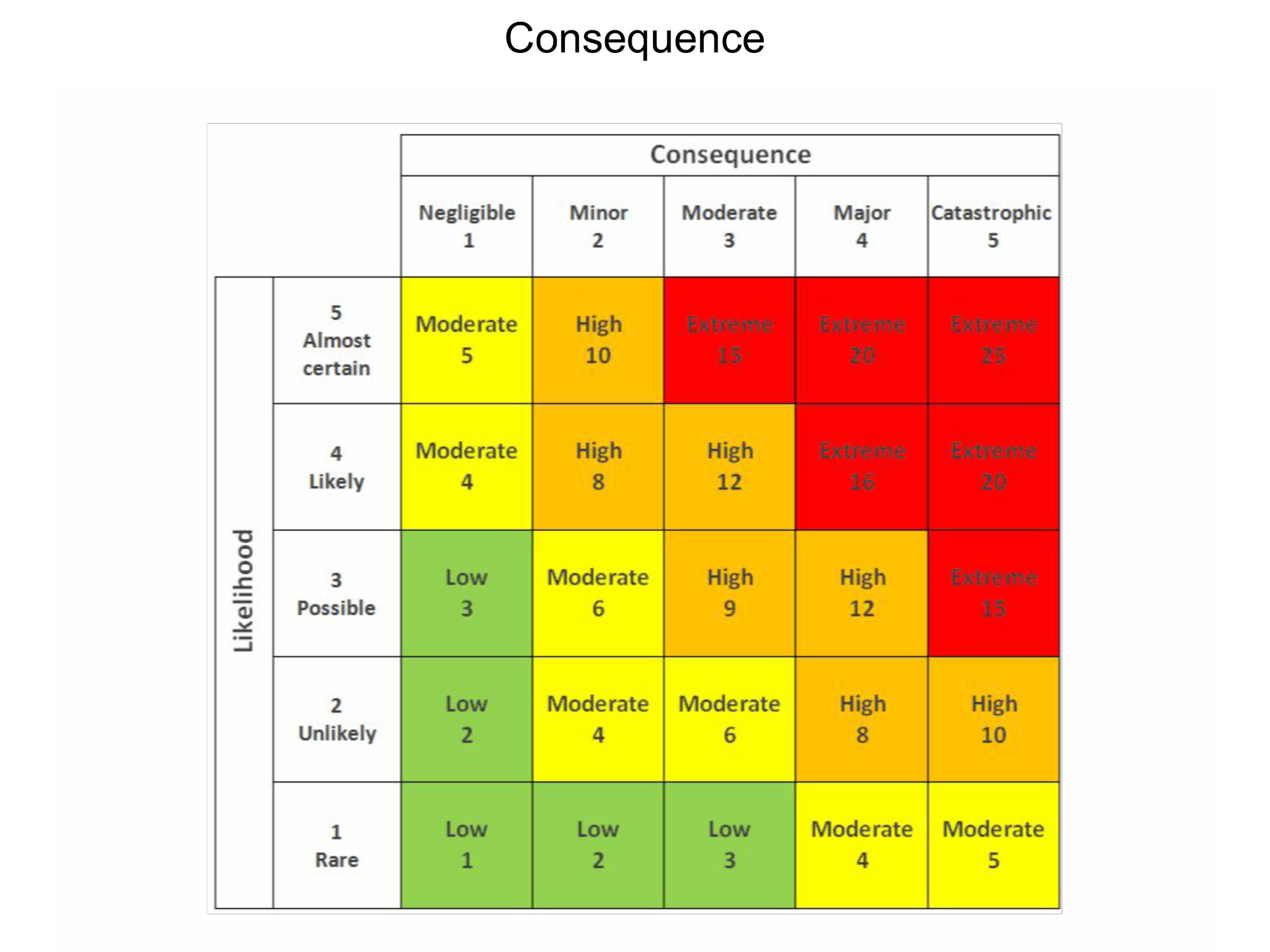

And "consequence" because I expect and am okay with some things going wrong. I just want to make sure they aren't high-consequence mistakes.

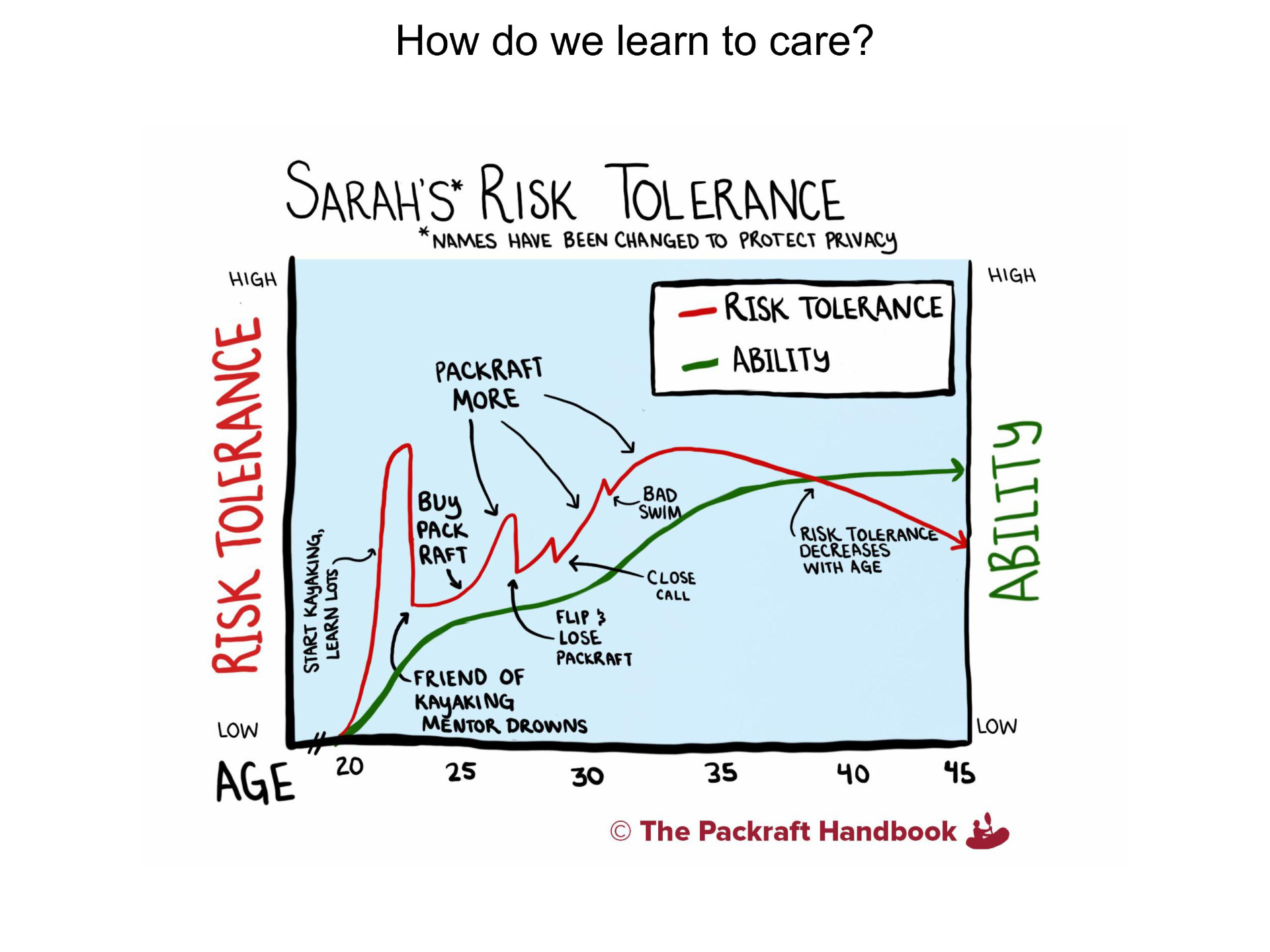

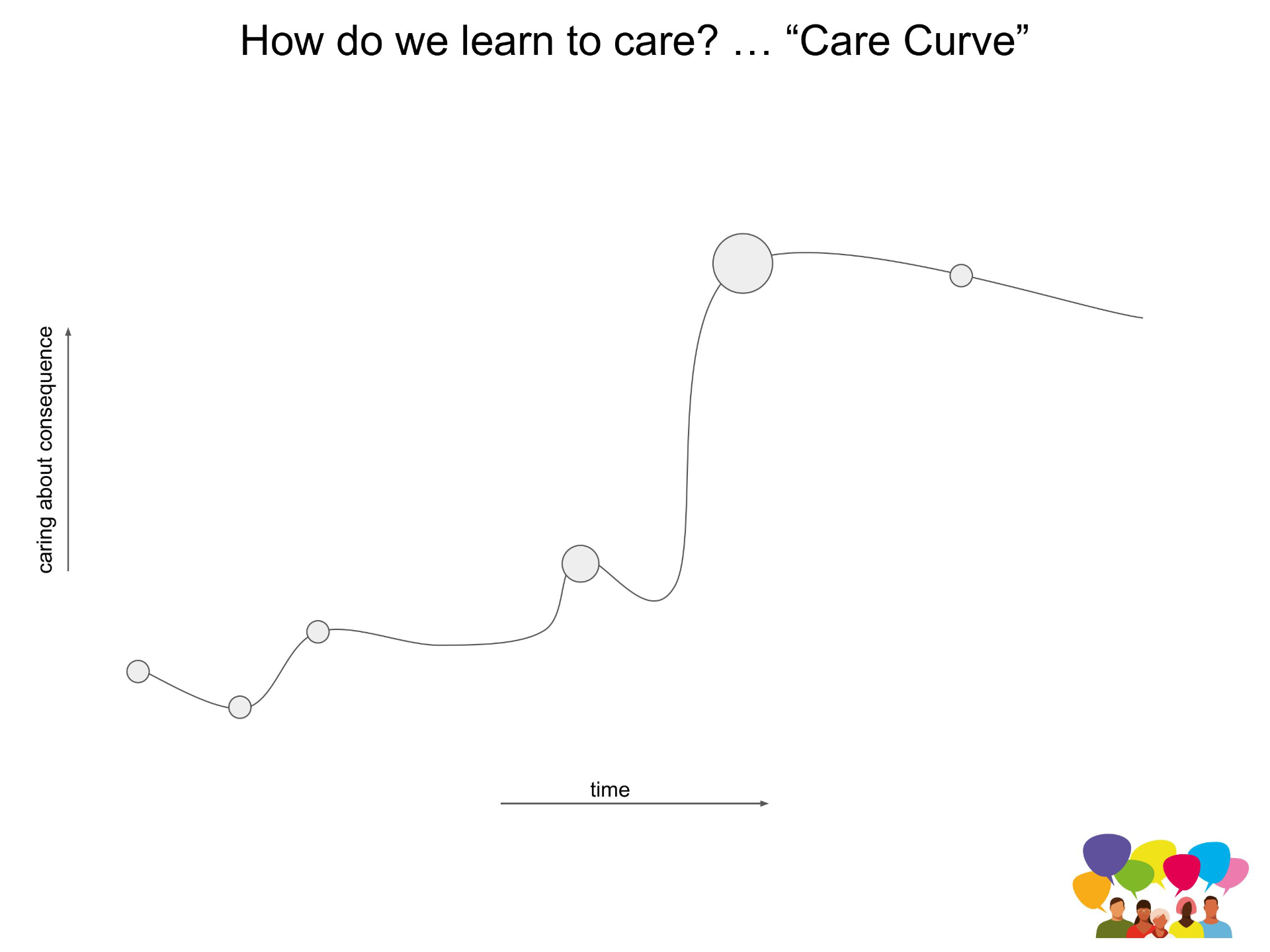

Take a few minutes to plot your 'care' history. Don't feel limited to recreation/outdoor space ... this could be other life events that have changed how you think about challenge, consequence, etc.

Try to track the relative significance of different events—I tried to do this by using different-sized circles at my anchor points. My medium circle was getting buried in an avalanche. My large circle was losing a friend to drowning.

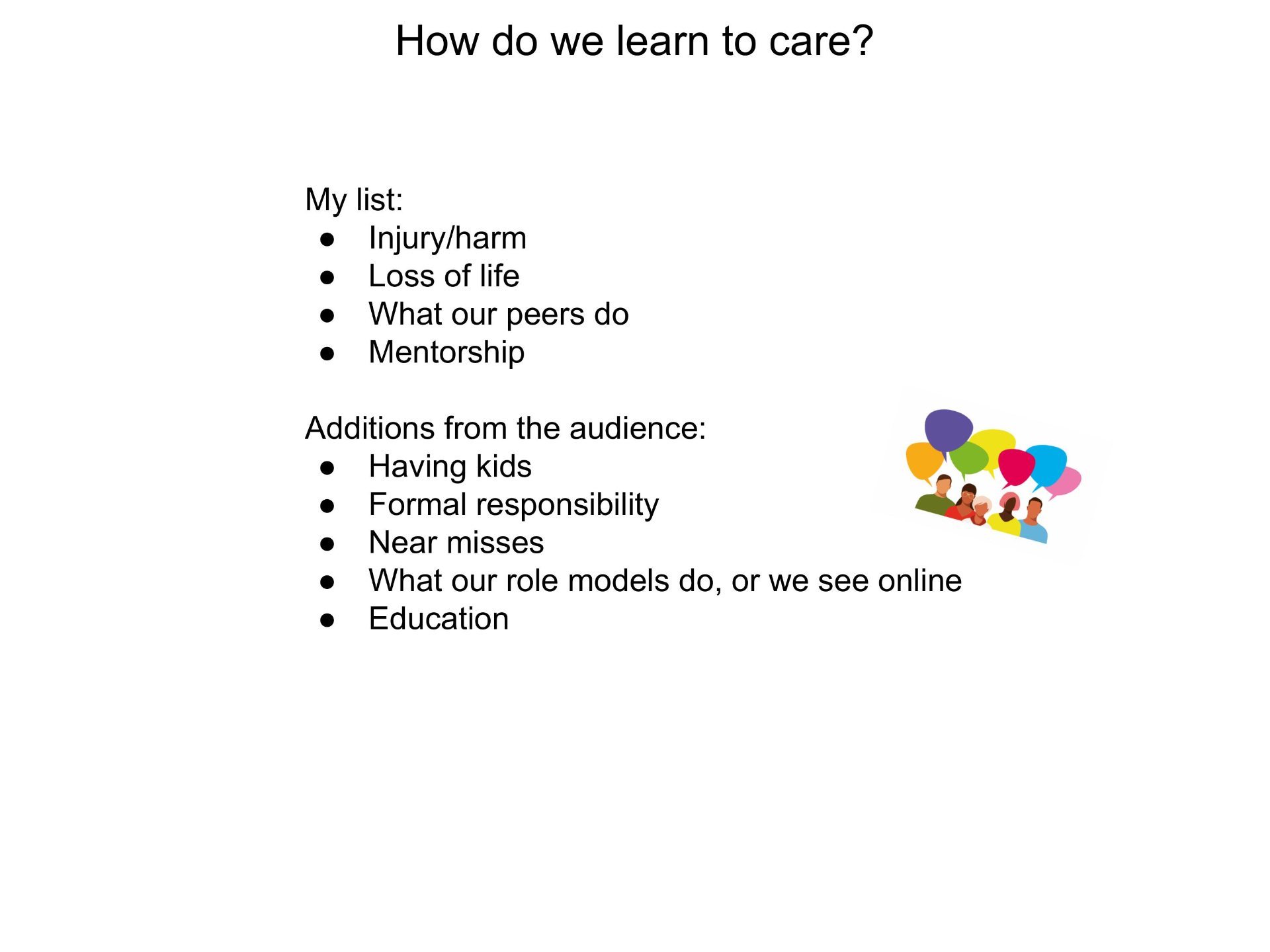

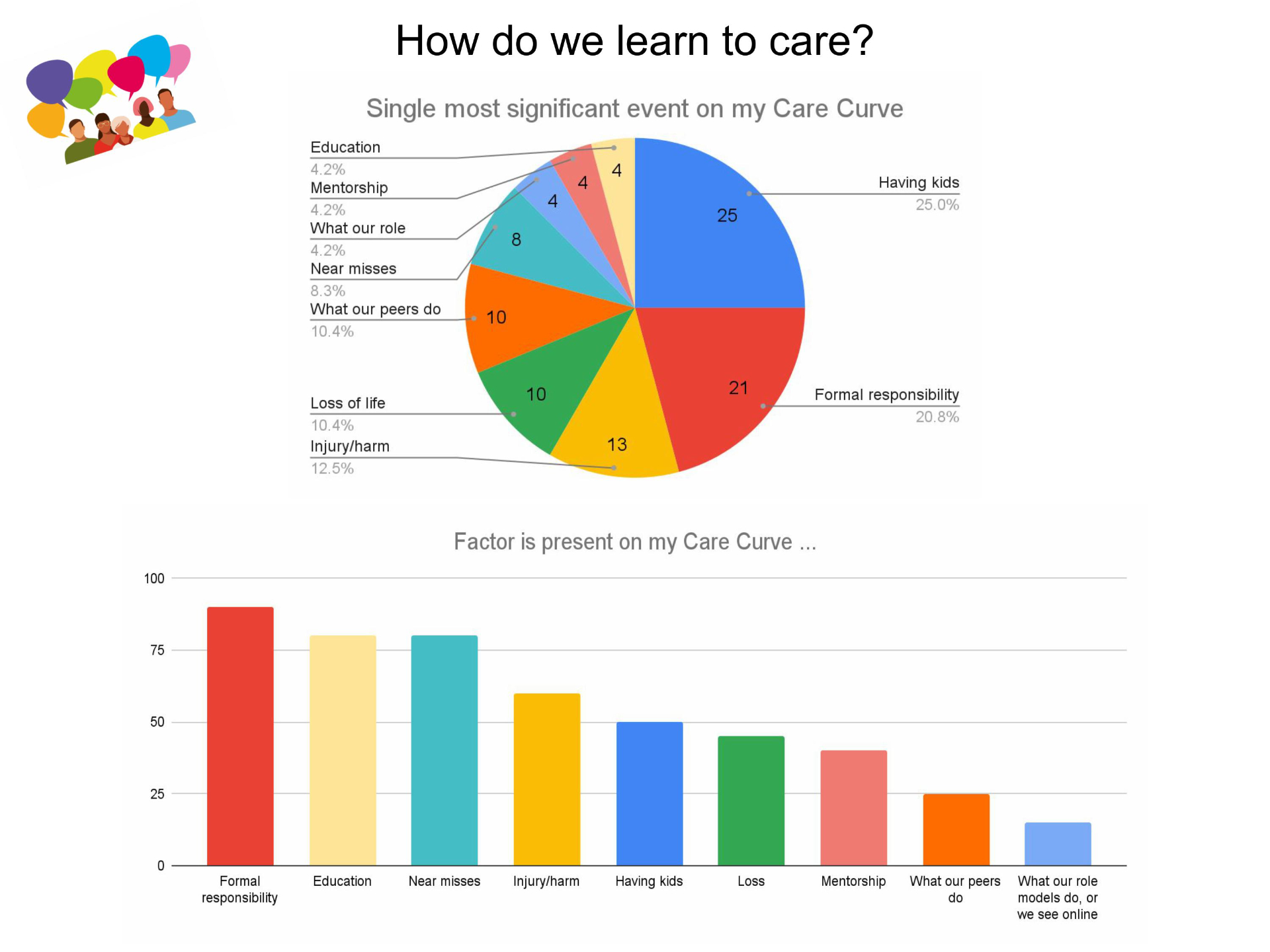

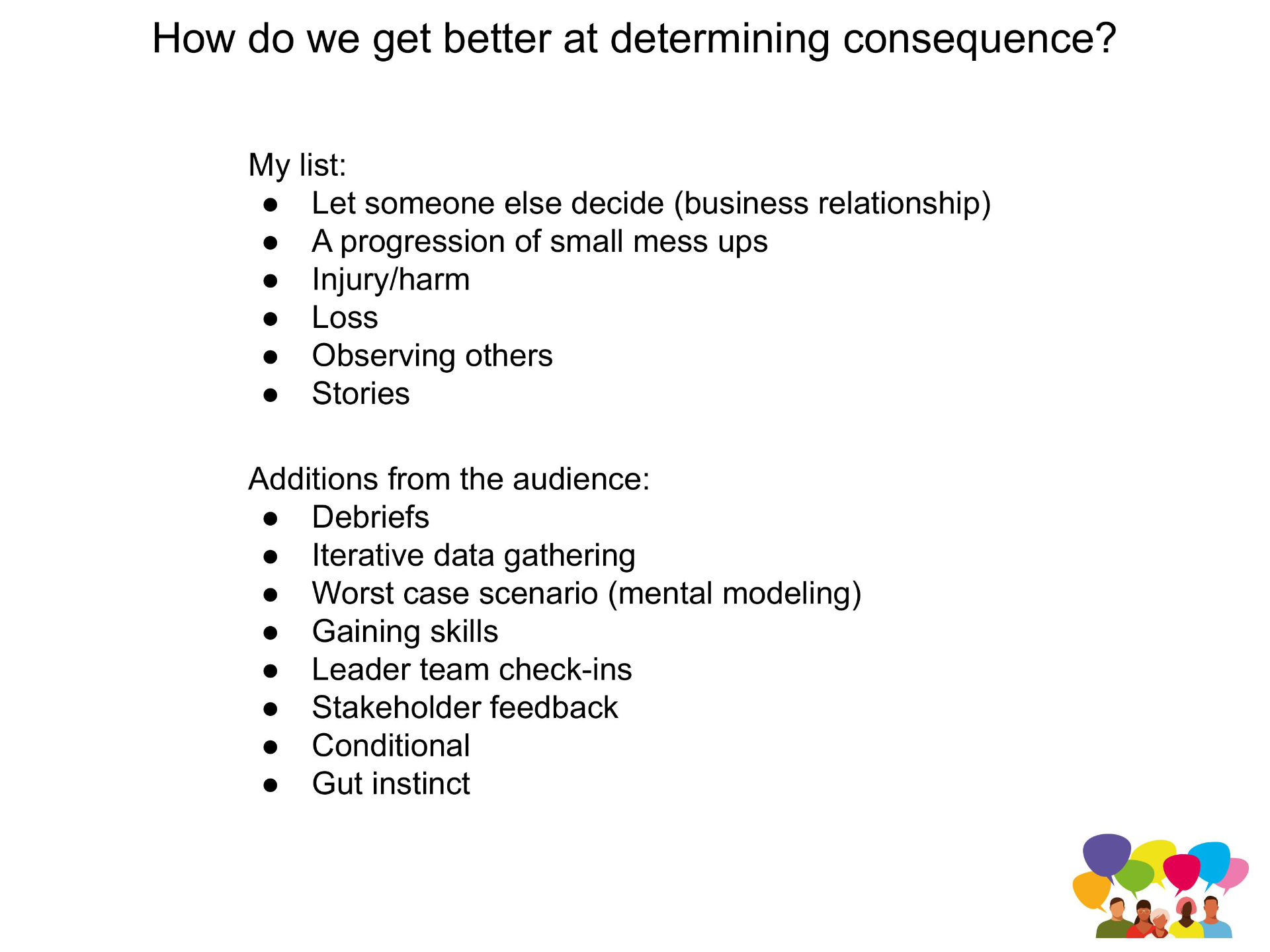

I provided a list of my factors and then solicited others from the audience.

Byron (I think this was not his name ...) helped run quick statistics from the audience.

I was missing the two most significant factors for the audience! Having kids and formal (professional) responsibility for others.

A few observations based on these results:

- Lived experience is by far the most significant influence: having kids, events at work, injury/loss of life, etc.

- Education, mentorship, and peer observations are "slow burn" contributors. They matter, but not as much and not as significantly.

- Education played a role in most people's "care curve," but was a significant factor for only a few people. This makes me think ... it is useful, but we shouldn't expect education to make a significant difference.

- What we see our peers do, social media, etc., was not particularly significant. I've been giving this too much weight.

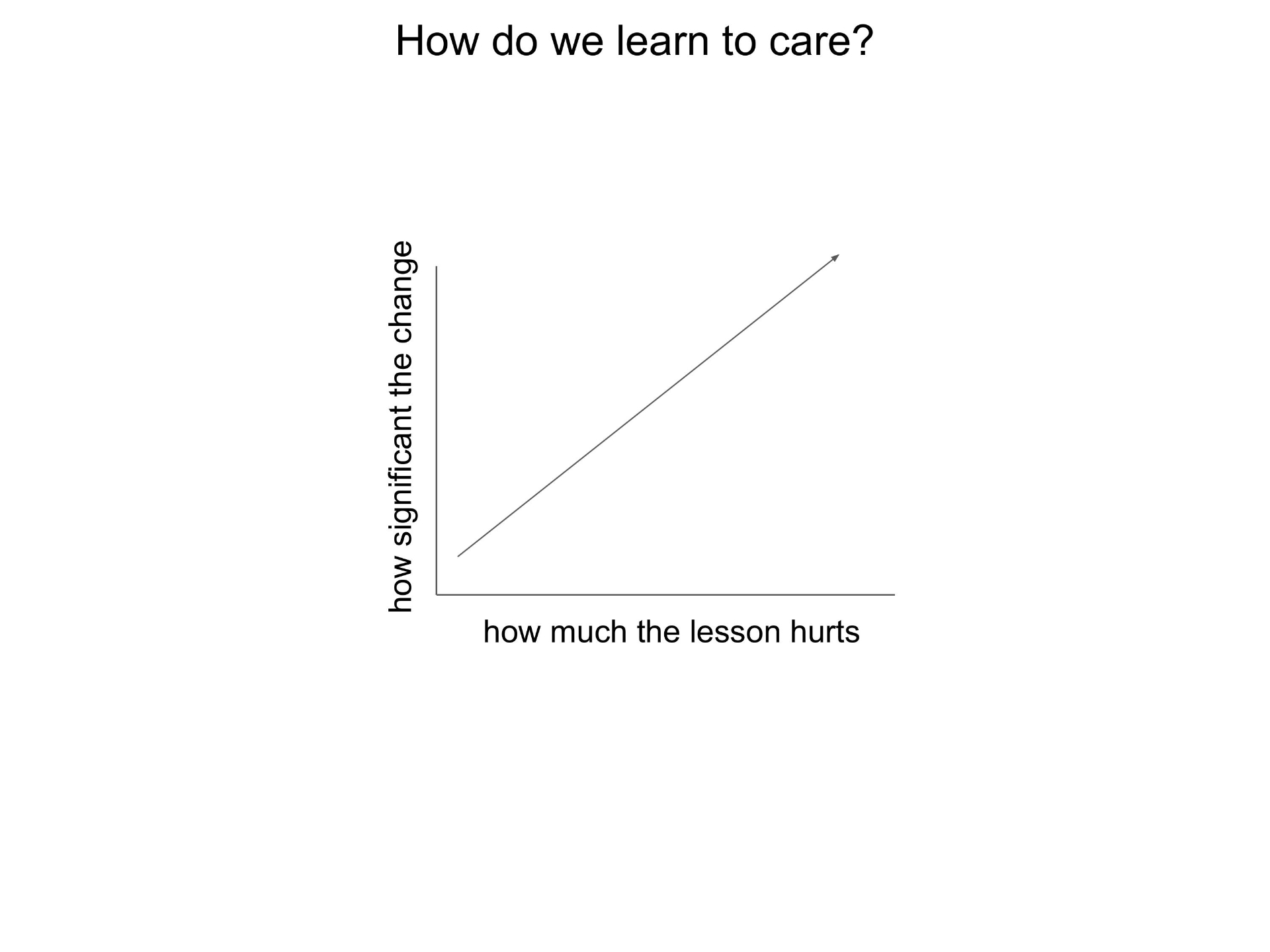

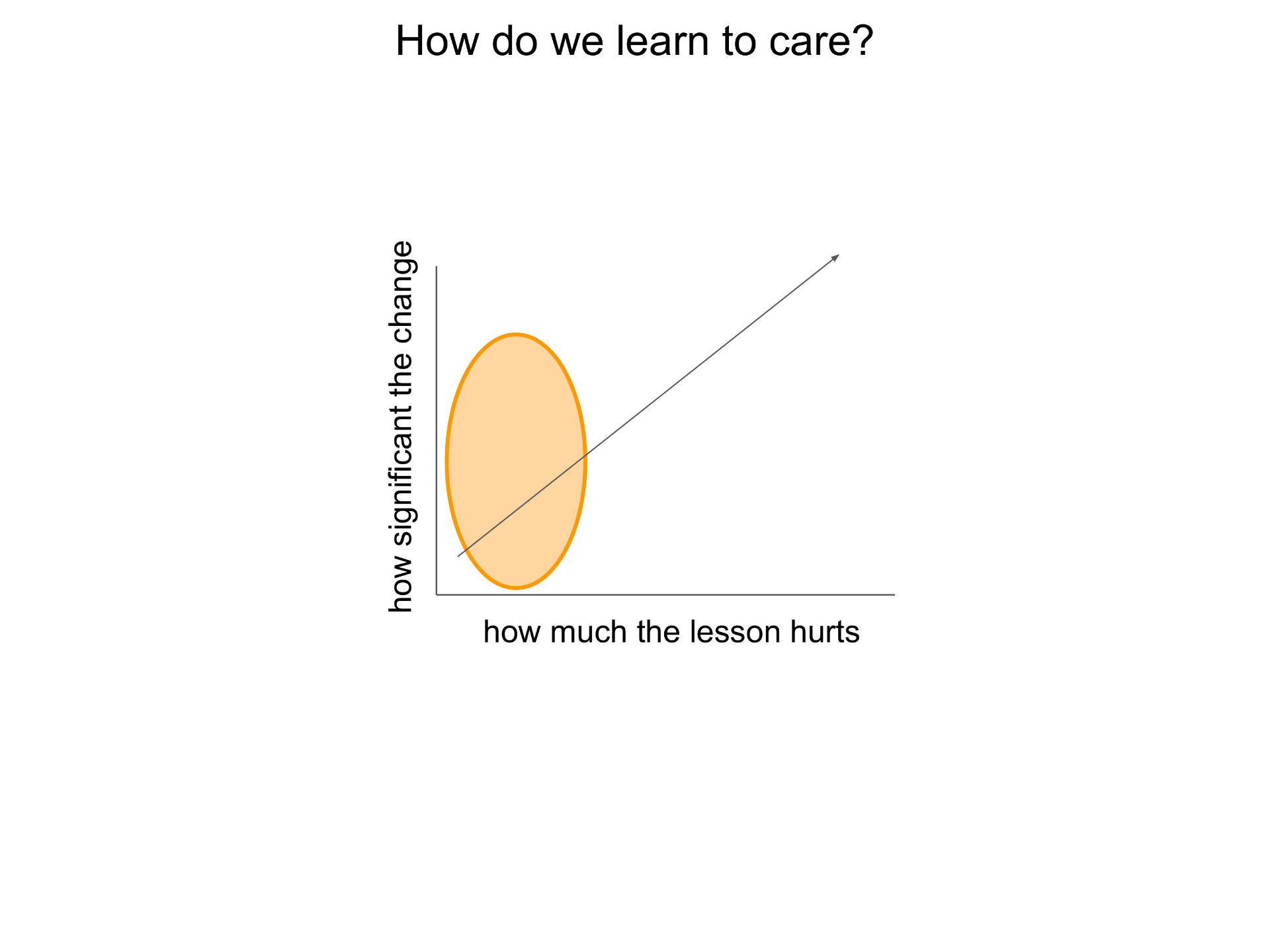

We can't expect to change much with the big hitters—they are always going to be devastating. And that's probably a good thing ... we should change behavior after significant events.

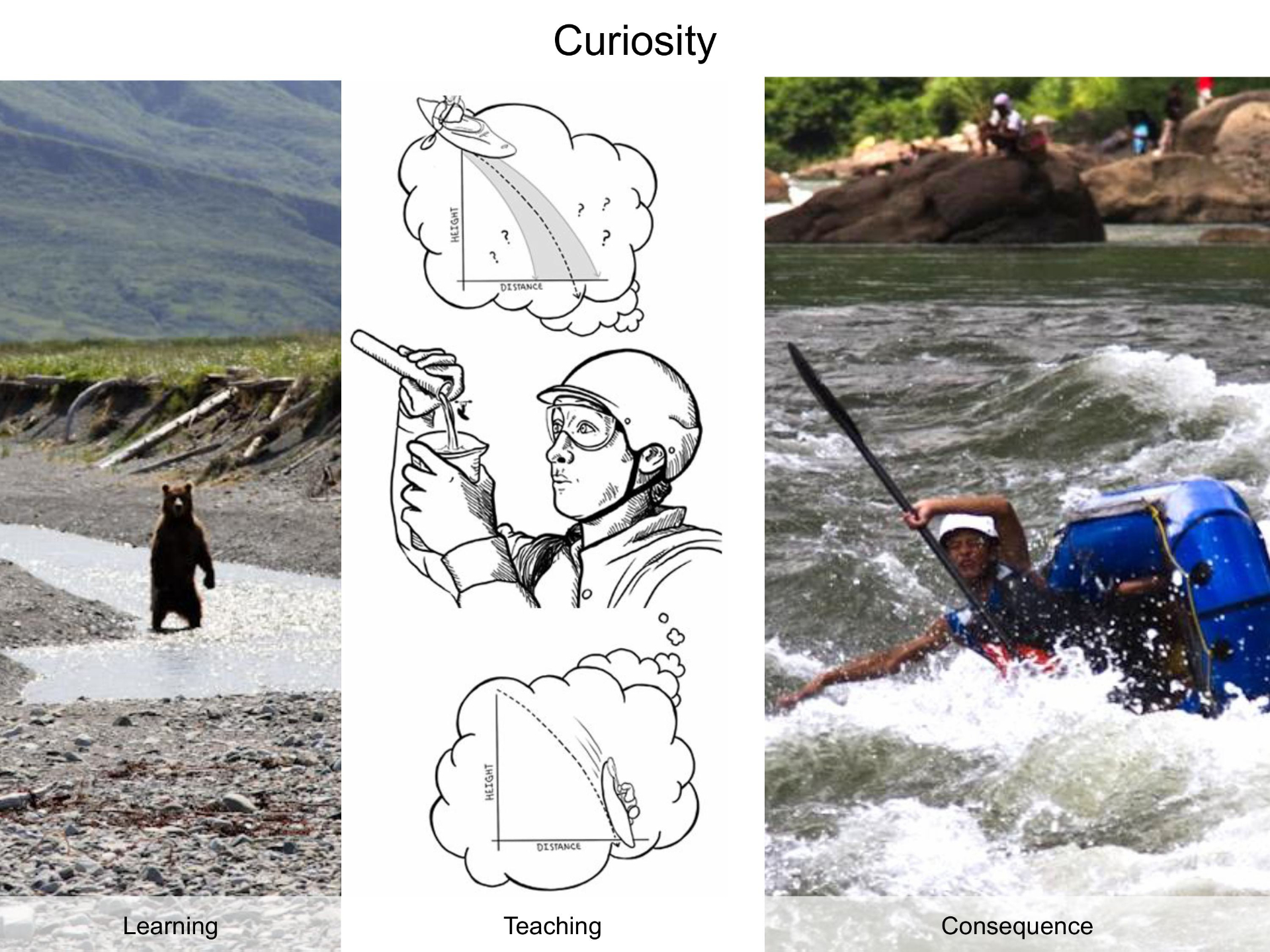

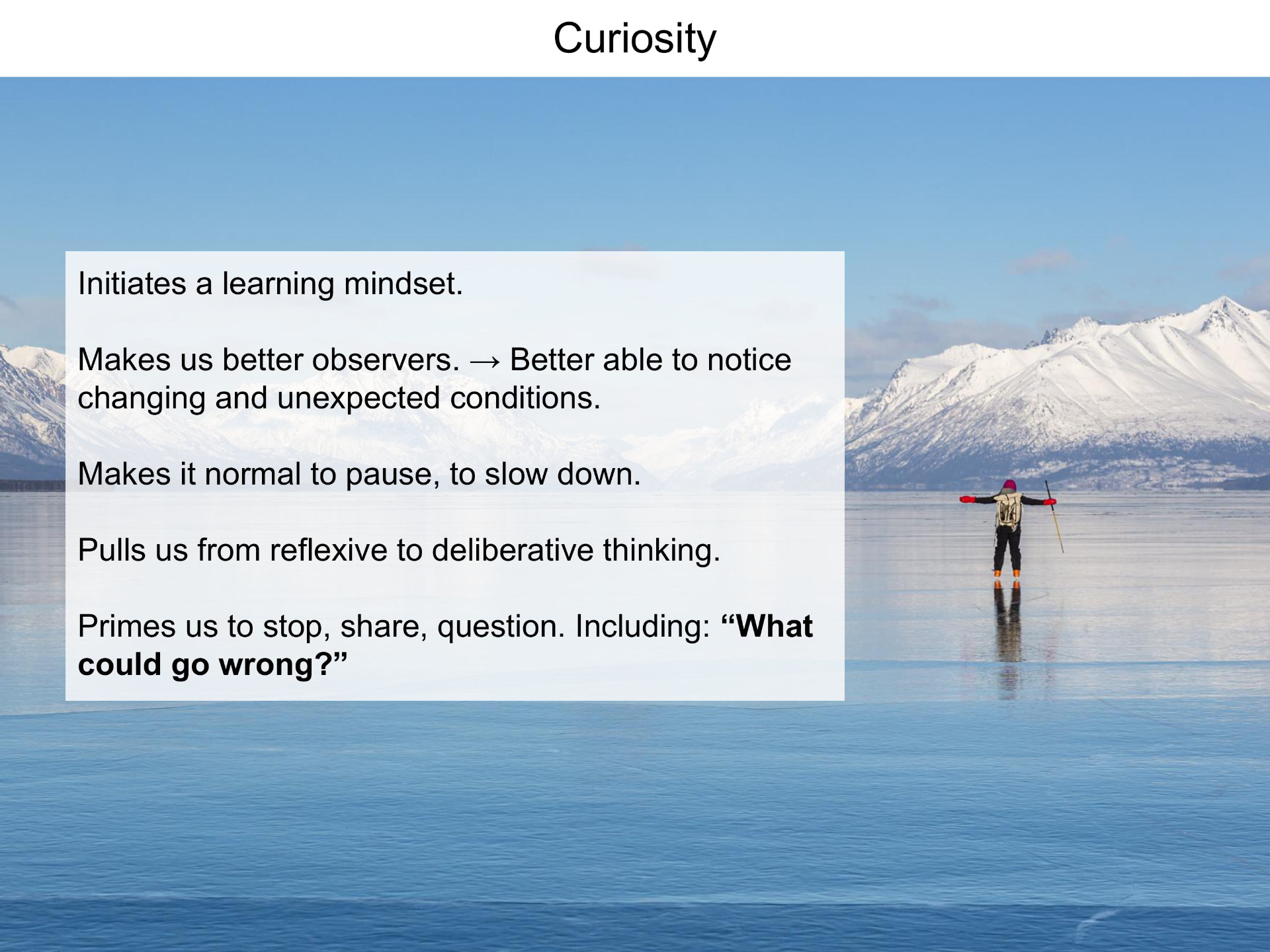

But maybe we can change something at the other end of the scale? I propose that curiosity can help us care more and be safer, without painful lessons.

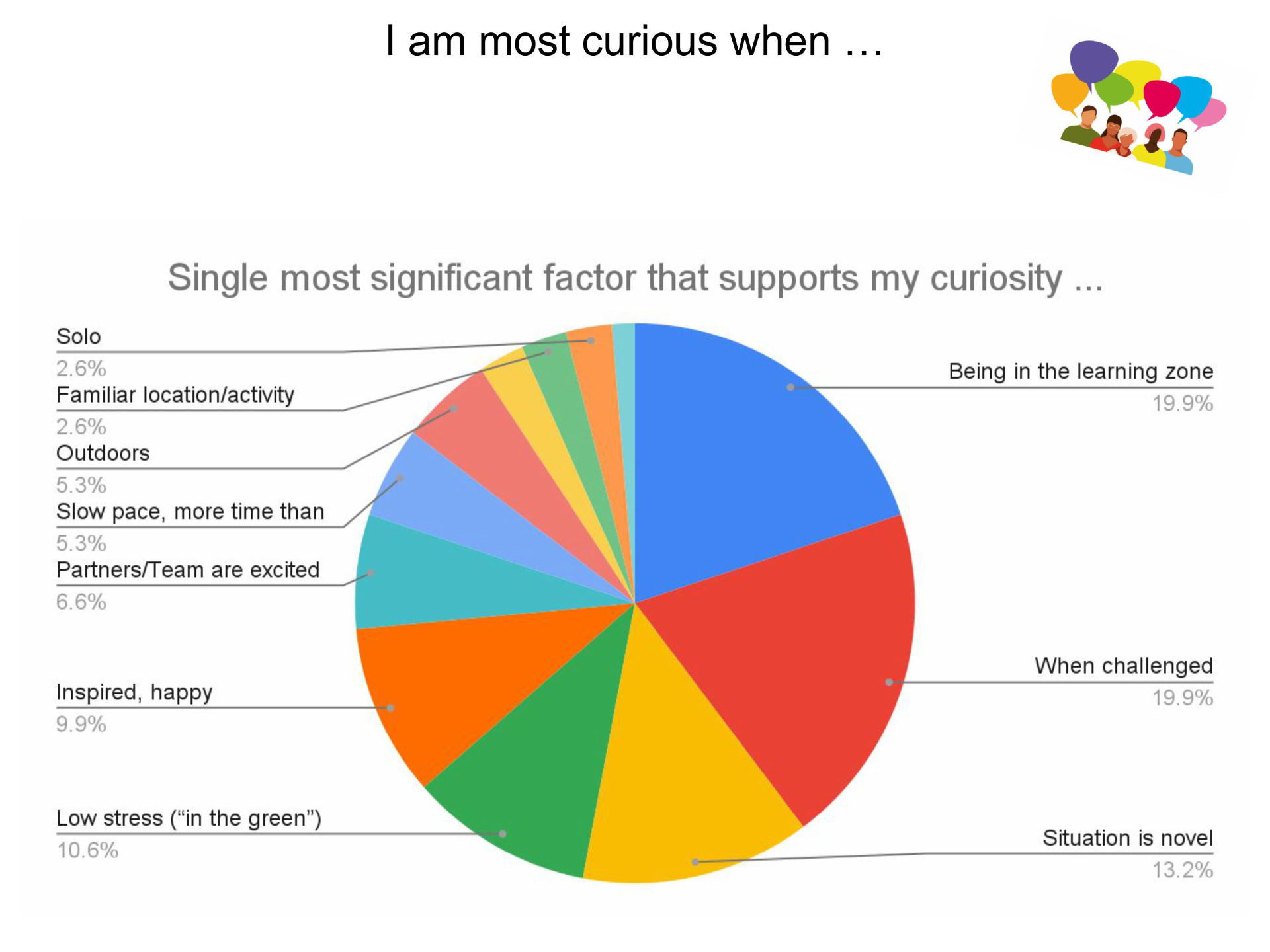

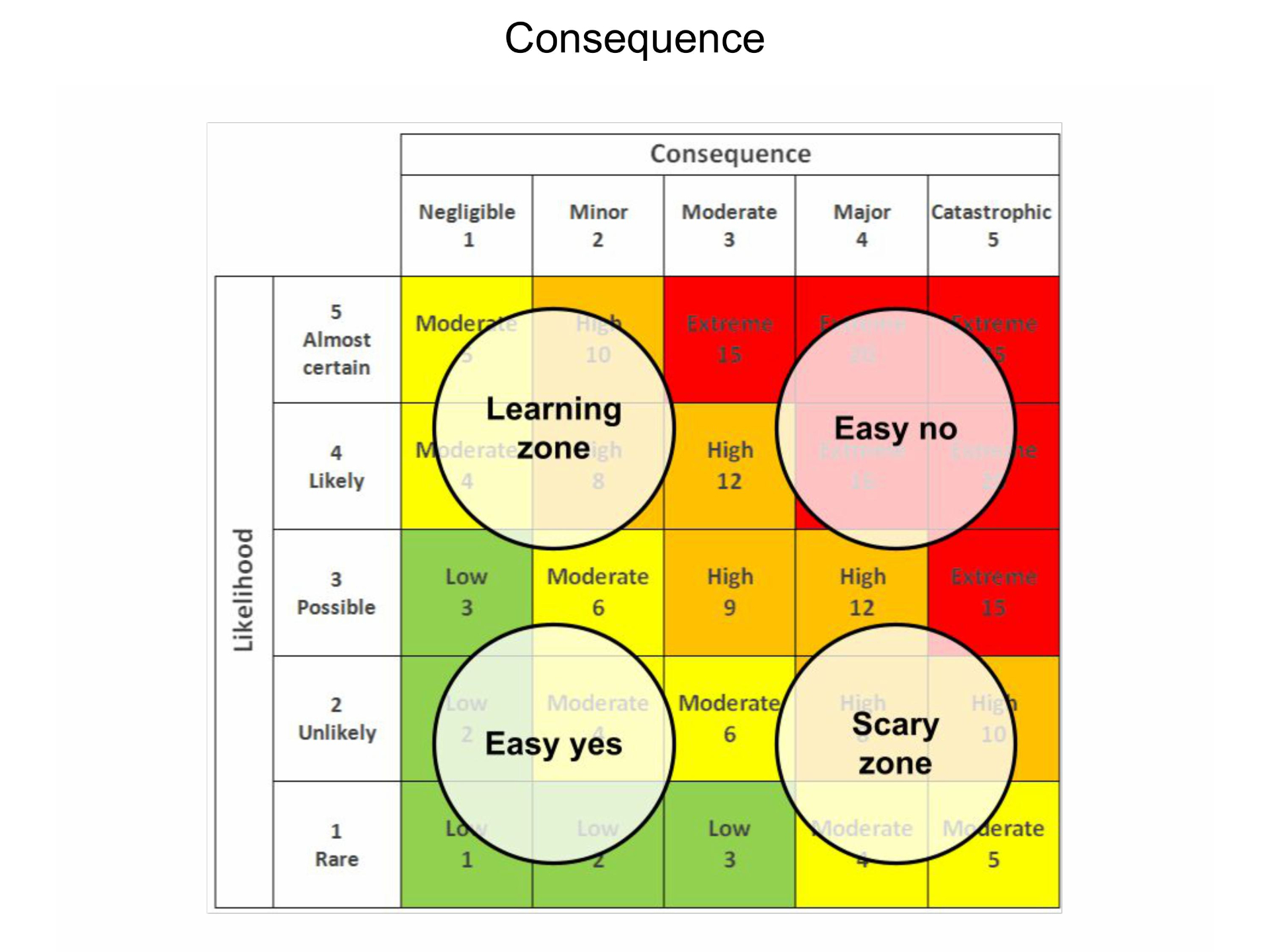

I love that learning zone, challenge zone, and novel, new experiences dominate this space. This is what we are trying to provide in outdoor programs.

A story: Sarah and I were highly observant, spotting animals far away, etc., while route-finding off-trail in the Eastern Alaska Range. After a few days we ended up on some mining-related ATV trails. After a short time on the trail we noticed that we were both thinking about chores/projects/politics and not as observant about our surroundings—not as good at noticing changes, remembering to make noise for bears, etc.

A story: This summer, Sarah spent 12 days in the Brooks Range with a few girlfriends before I flew in and her girlfriends flew out. Sarah's time in the mountains had already built up her "backcountry brain" AND her legs were already in hiking shape. She had more capacity for curiosity and was better at pointing out bird nests, bears, route options, etc. I had a heavy pack and mostly put my head down to just get the job done.

Let's play "big deal / little deal?" This guy just fell in a crevasse. Big deal or little? He also had a hot spot on his foot that turned into a blister in the next days. Big deal or little?

We managed the crevasse well ... the rope was tight, he barely broke through. But the blister became a big enough deal that we canceled the trip, backtracked, and chartered a flight out of the mountains.

No wonder it is hard to get this stuff right!

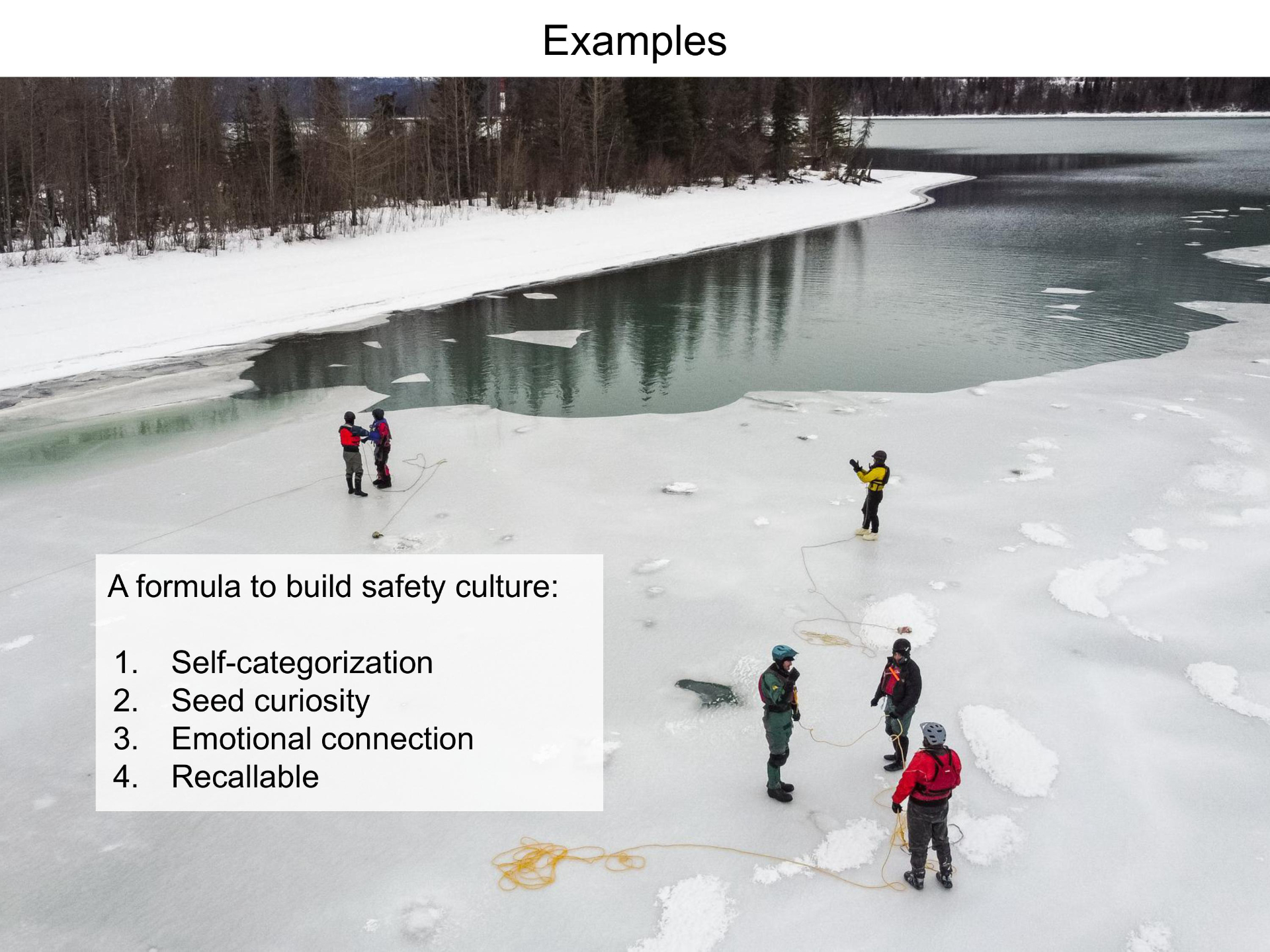

A story that captures how curiosity resulted in a valuable insight about thin ice:

We were ice skating on sea ice in NW Alaska when we noticed some chunks of ice on the otherwise smooth surface. This was just a day outing, small packs, and the travel was easy, so we had a lot of space to detour and check out points of interest.

We skated over to the blocks of ice and noticed a crack pattern and that there had been an open hole. It took a while to figure it out, but this is where a seal created an air hole by striking the ice from below.

Not only did this observation add a cool layer to what was already an amazing day, but it also informed us about thin ice. The seals were breaking through the thinnest ice possible, and the correlation between air holes and thin ice allowed us to avoid thin ice for the rest of the outing.

It has been incredibly rewarding to watch a successful safety culture campaign within the global packrafting community. When I try to distill what has worked, these are the four key factors:

- Self-categorization: Maybe this could be called community or sense-of-belonging, but the key is that we need to personally identify with a group in order for the messaging to feel relevant. Group size matters.

- Seed curiosity: Plant a seed that invites interest. I'll use examples of art below.

- Emotional connection: Find a way to make the message relatable, for the recipient to feel connected to the experience. Stories are probably the most effective option.

Recallable: We want the lessons to pop up when needed. Stories work, and maybe visual reminders, too, like stickers.

- Self-categorization: Apparently, the packrafting community is the perfect size for a safety culture campaign. I knew people were eager for this resource, and I knew how to reach them. I was turned down by a publisher but went forward anyway, taking a year off work to write the book and then draining my bank account to self-publish it. It has now sold 10,000 copies.

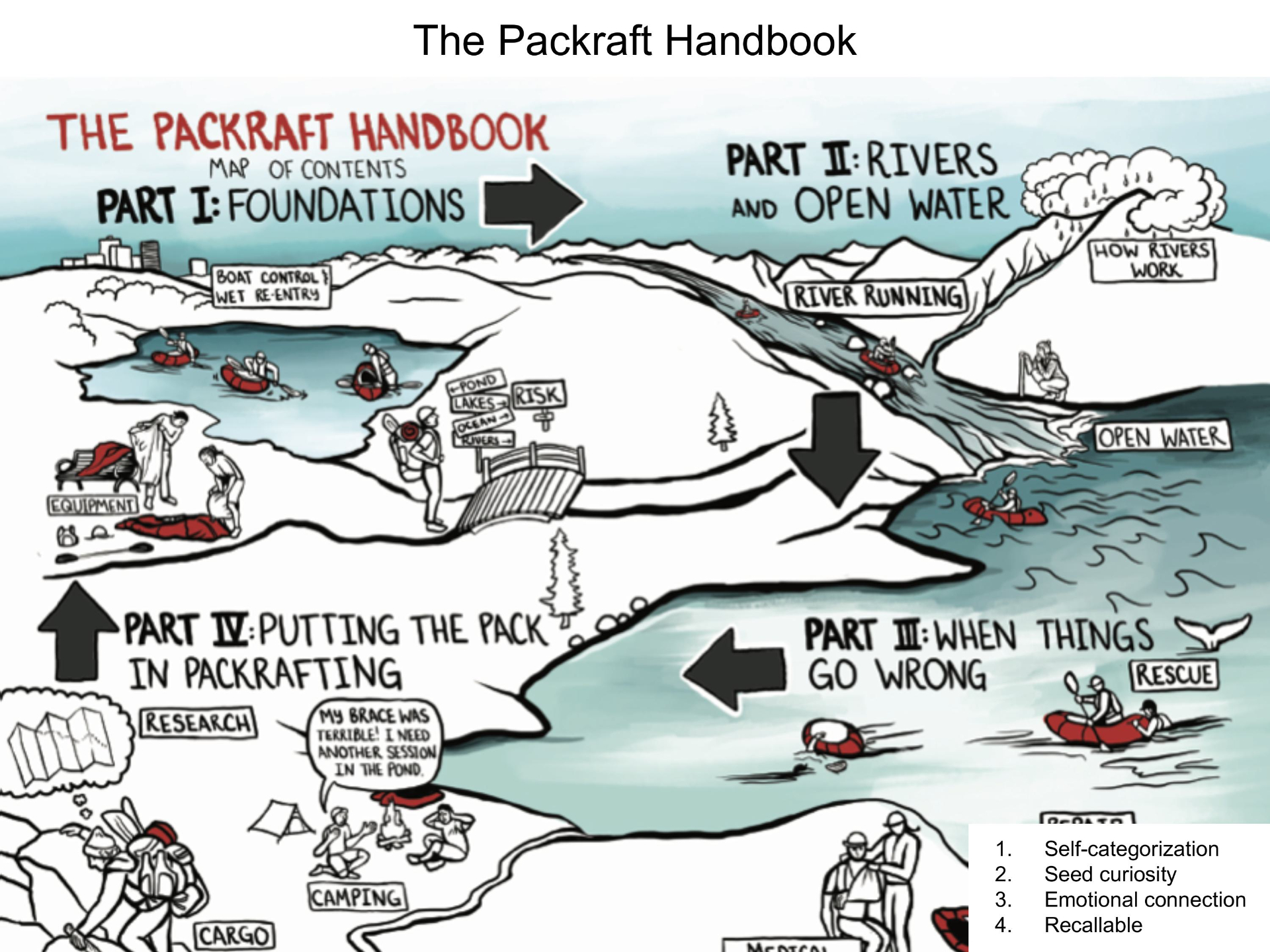

- Seed curiosity: I wanted to plant a seed for curiosity right away, so the book opens with a fun "map of contents." Our hope was that the illustration would pique interest, motivate people to follow the arrows, and get excited for the content.

- Emotional connection: I write about Rob's drowning in the preface. People know where this is coming from, and they feel sympathy for the loss.

- Recallable: Memorable artwork and stories throughout.

I consulted with Molly Golden, a graphic designer to figure out how to "seed curiosity" on nearly every spread in the book—each spread has a photo, illustration, or shaded text inset box. Our hope was to pull visual interest, which might motivate folks to read the text around the image, the next page, etc.

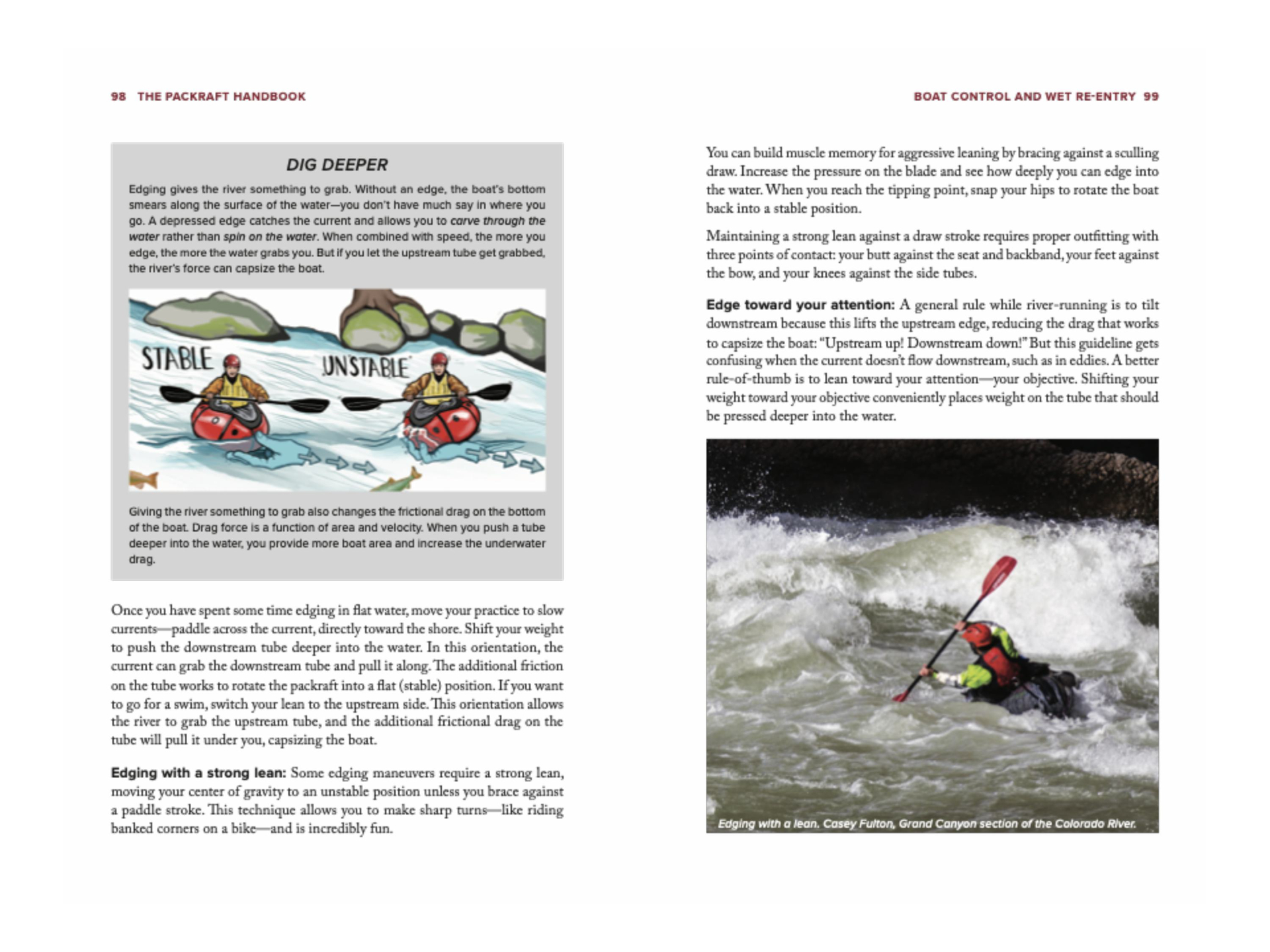

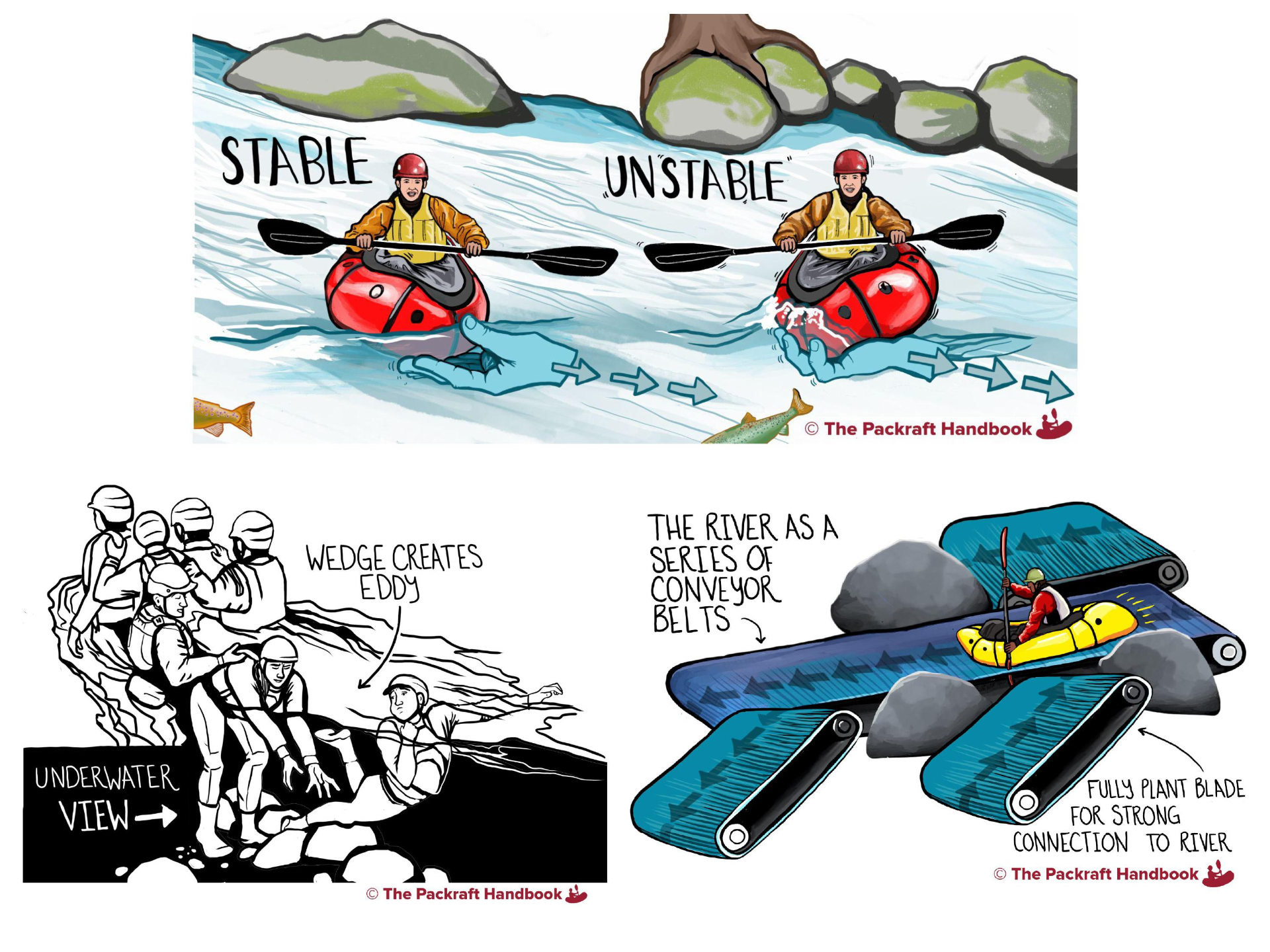

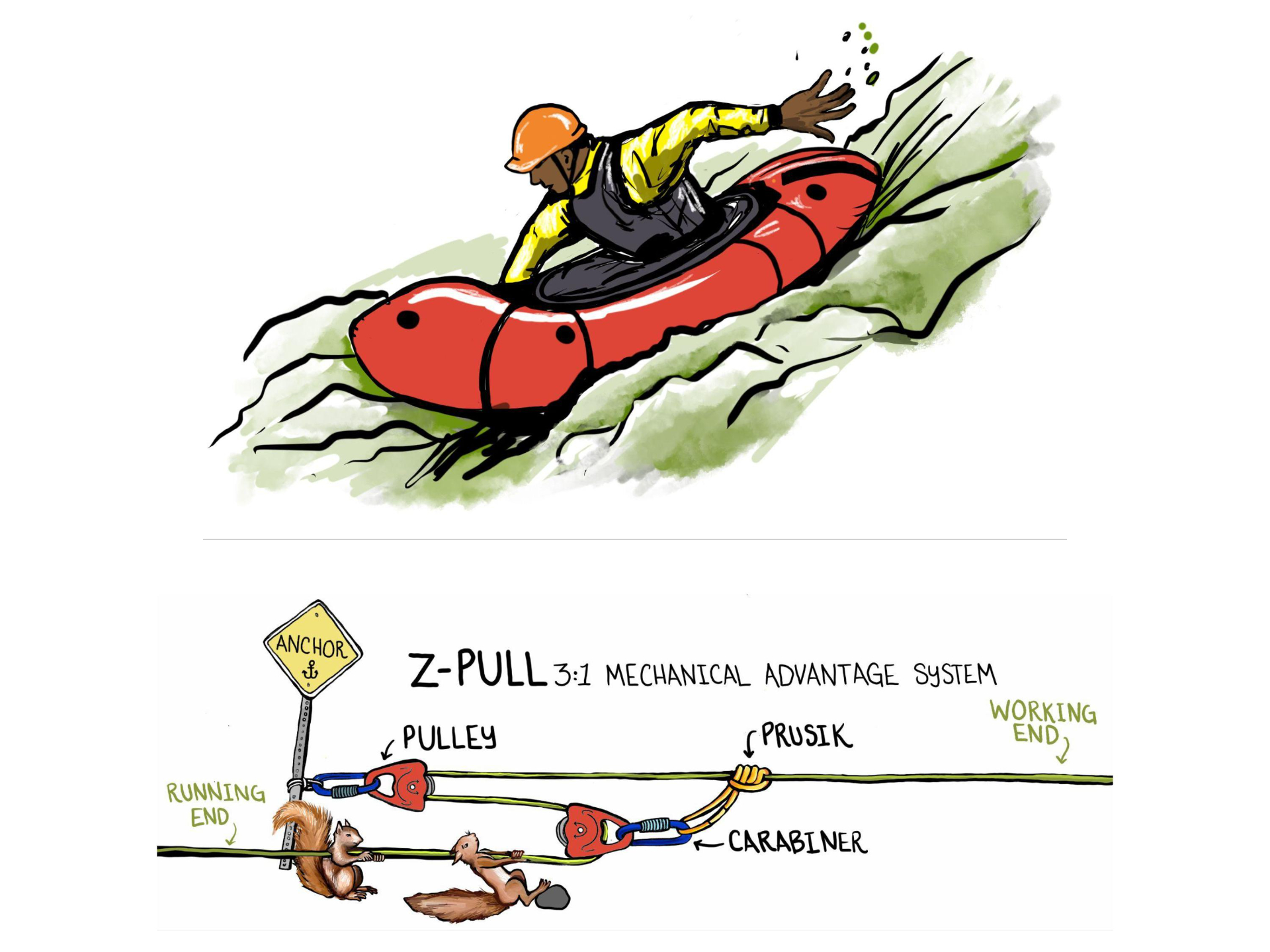

I had planned to use photographs for the book, but Sarah K. Glaser convinced me that her illustrations were significantly more effective as teaching tools. She explained:

- Can show multiple frames at once, e.g., the motion of a paddle.

- Can reveal what is happening underwater or in x-ray view

- Can emphasize details. For example, the hand shown in the hand-paddling illustration below is enlarged to emphasize it.

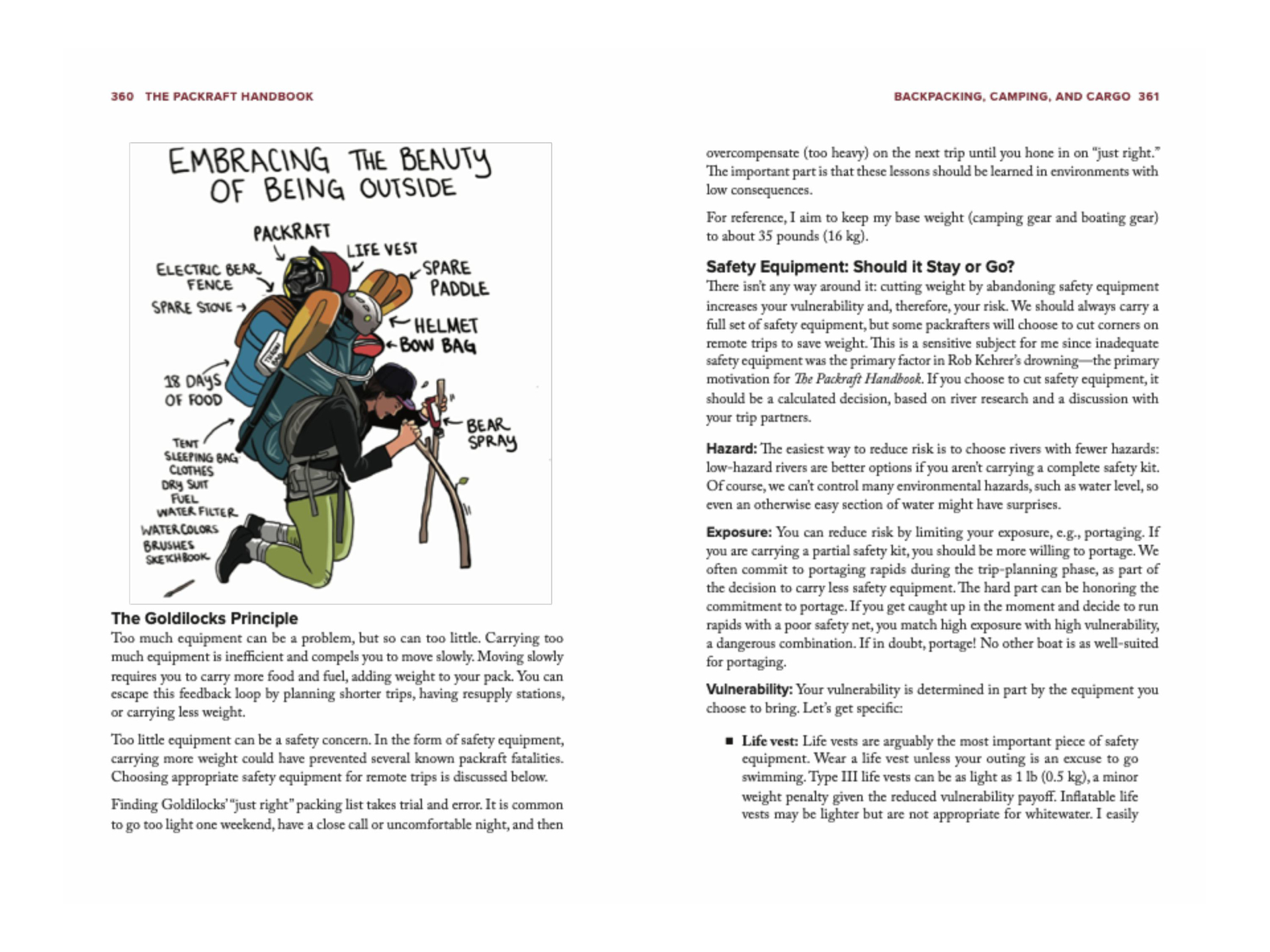

What I did not realize at the time, which is possibly the single most important cause of the book's success, was how Sarah's creativity, humor, and inclination to include little treats (squirrels, puns, etc.) would seed curiosity throughout the book. We worked off each other through multiple iterations to get the tone of the text to match the illustrations and vice versa.

Our success with The Packraft Handbook earned us the opportunity to work with American Whitewater (AW) on a revision of their Safety Code. The Safety Code was written in 1959 and has had several major revisions since. Our team was tasked with converting the code from a long text doc to something more accessible.

- Self-categorization: One of our challenges was to create something that resonated with different types of river runners. "River runners" is what AW has identified as the most inclusive term ... "paddlers" excludes oars-folk, "rafters" excludes others, etc. In contrast to packrafting's very strong sense of self-categorization, this felt like a wide net—unlikely to be as effective.

- Seed curiosity: Sarah's art was the key here. Because this was a more technical document, it lacks the stories, relatability, and some of the quirkiness that Sarah brought into her illustrations in the packraft book.

- Emotional connection: Not much of this. My attempt at emotional connection was to justify the talking points in data from the AW Accident Database as much as possible. The code starts with "The Big Four" causes of incidents as identified in the database. These are featured on hangtags, stickers, and other products as well.

- Recallable: Illustrations, but otherwise, not much.

I'm proud of this work; we did a good job, and the safety code is packed with good information. But I don't believe it will be as effective at changing behavior, even if it reaches a wider audience.

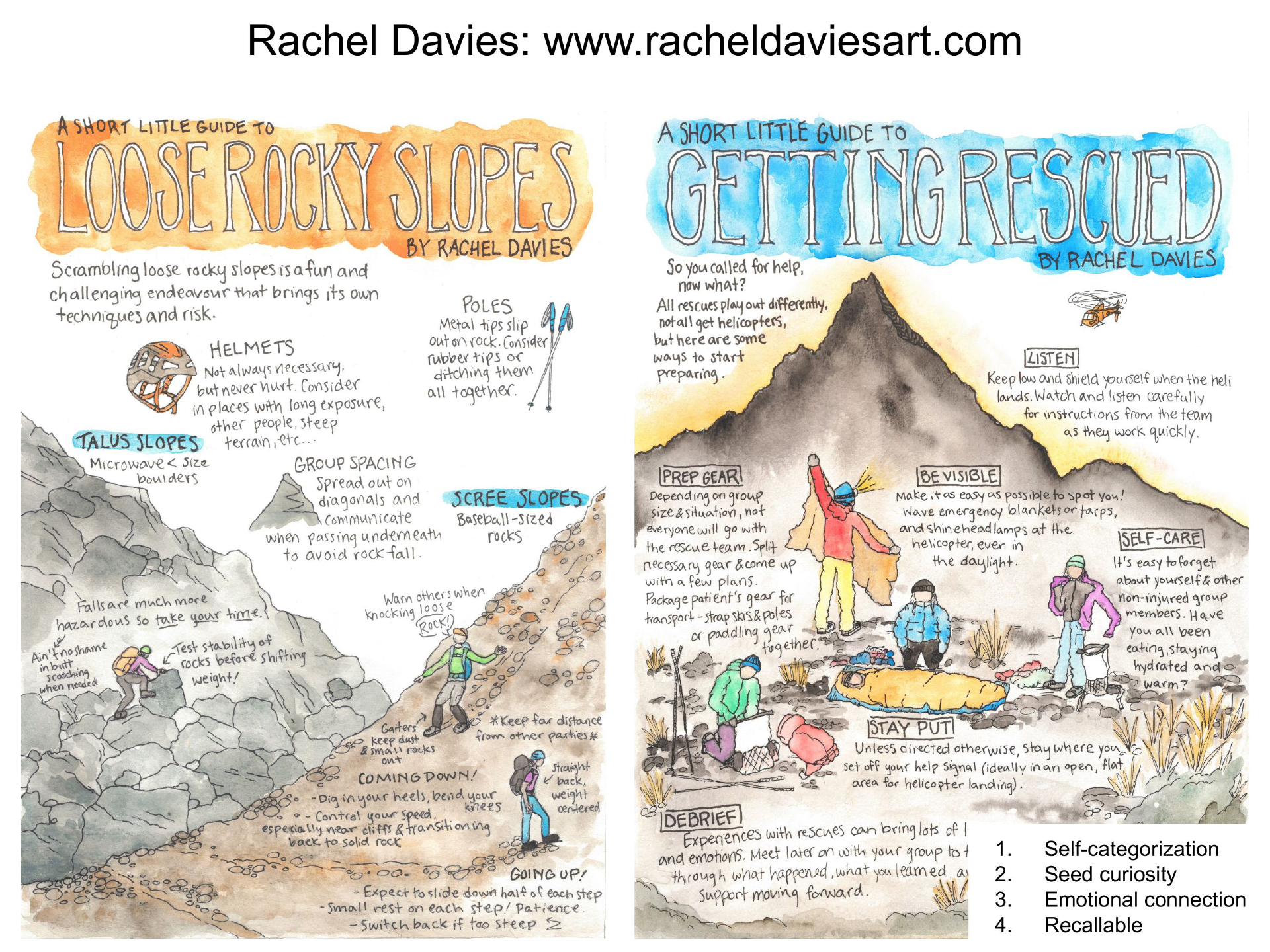

Rachel Davies is an artist in Alberta. I love her watercolor and handwritten style. Let's take a look at how her work fits the four-point safety culture wishlist.

- Self-categorization: Rachel's work covers many topics. It might have the most appeal to backcountry hikers, who are a large community and hard to reach directly. Social media algorithms help here: the folks who like Rachel's work and similar topics are going to be fed more of it.

- Seed curiosity: Rachel's style draws my attention to the different pockets of activity. The level of detail works for me too ... short enough that I'm willing to read it before moving on to the next thing.

- Emotional connection: This is hard to do without stories!

- Recallable: I don't know how recallable these are. But they are a great addition to the model of learning where repeated exposure makes it start to stick.

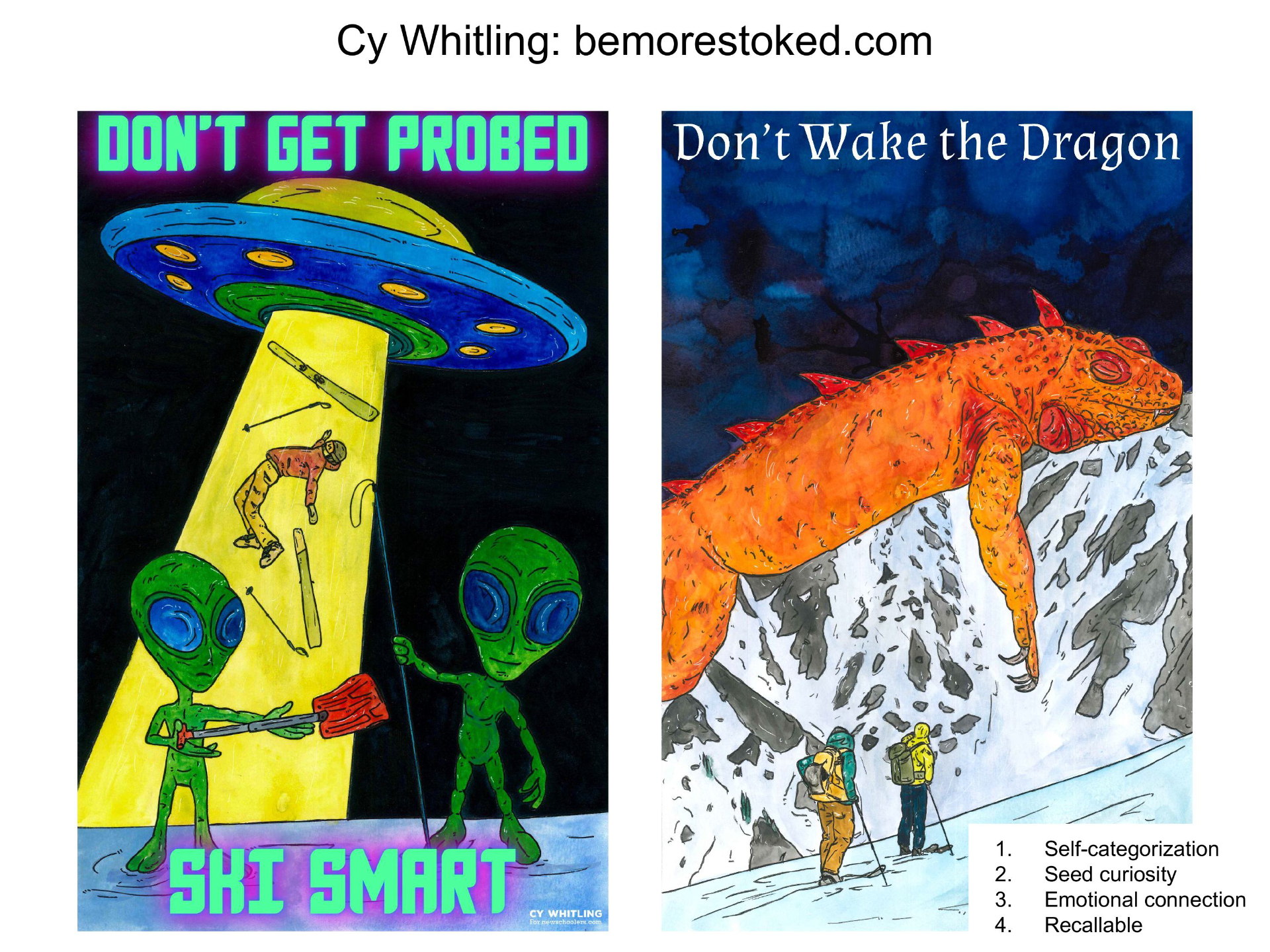

Cy Whitling is an artist in Bellingham. You know the drill:

- Self-categorization: In this example, Cy takes a different approach than Rachel: he uses terms and concepts that will only make sense to "insiders." You have to already be a backcountry skier to know what an avalanche probe is, or to know that the snowpack is sometimes referred to as a sleeping dragon. This targets the bc skier subgroup of skiers.

- Seed curiosity: Cy relies on humor and striking/contrasting imagery to pull in viewers. It works for me!

- Emotional connection: This is hard to do without stories!

- Recallable: These would be most recallable as posters at bc trailheads or stickers. Stickers are an excellent way to carry safety messaging with us.

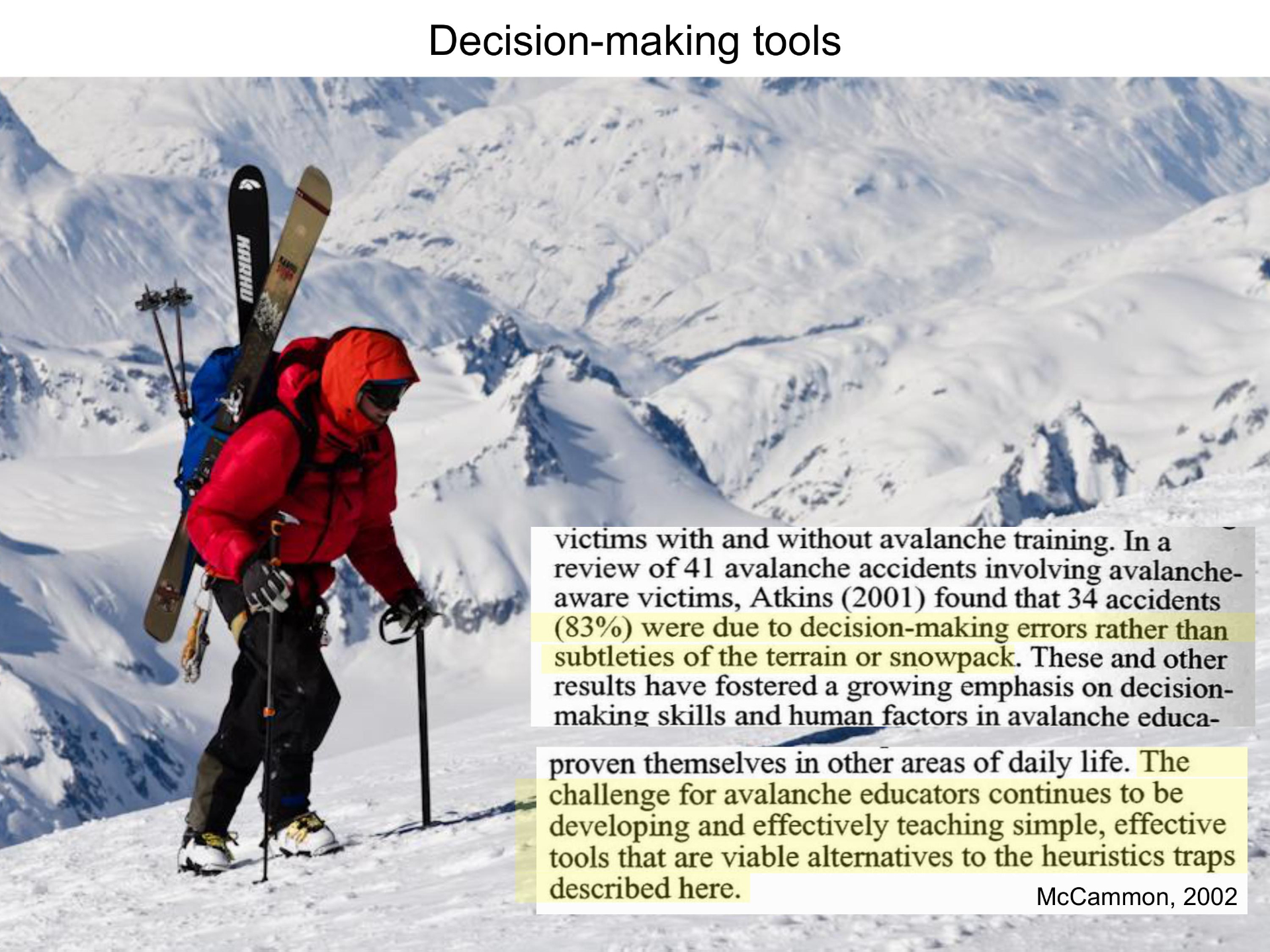

Our next examples are decision-making tools.

I first learned about this problem as part of my avalanche education: We know why avalanches happen and how to see warning signs, but we keep making decisions that get us in trouble. Ian McCammon (in the audience) has spent the past two decades working on this problem.

The most widely cited reference about decision-making errors (cognitive biases and heuristic traps) is Daniel Kahneman's Thinking, Fast and Slow. I struggled through this book and then was frustrated to read this at the very end: Awareness about these errors hasn't made the author any better at avoiding them!

I think Ian put it this way in his talk at the conference: These mental shortcuts work for us most of the time—we need them to get through daily routines—so it is a big ask to stop using them.

I want a toolbox ... action items that I can pull like cards from a deck to help me make better decisions.

The seed that sparked my curiosity to learn more about decision-making was part of Deb Ajango's wilderness medicine courses (safetyed.net, though the site is currently down for me). Deb incorporates brain science and, more importantly, stories that demonstrate that our brains can be unreliable when it comes to making the best decisions (and why).

The story that stuck with me (and that I tracked down in the book On Combat) is about a police officer training to disarm a person who draws a handgun. The officer is obsessed and practices with everyone in the unit, his wife, etc. He asks the person to draw, disarms them, hands the gun back, on repeat.

The officer is involved in a robbery at a convenience store. The robber pulls a handgun, and the officer disarms him instantly. He then hands the gun back to the robber. Because this is what he practiced.

That story piqued my interest in learning more about my brain and how to avoid similar mistakes!

- Self-categorization: This will depend on the target audience. The photographers and the kayakers in this photo need different messaging.

- Seed curiosity: "Gosh, our brains are weird" works for me. It might not work for you.

- Emotional connection: We need relatable (heartfelt? funny?) stories that convey the point.

- Recallable: Memorable stories.

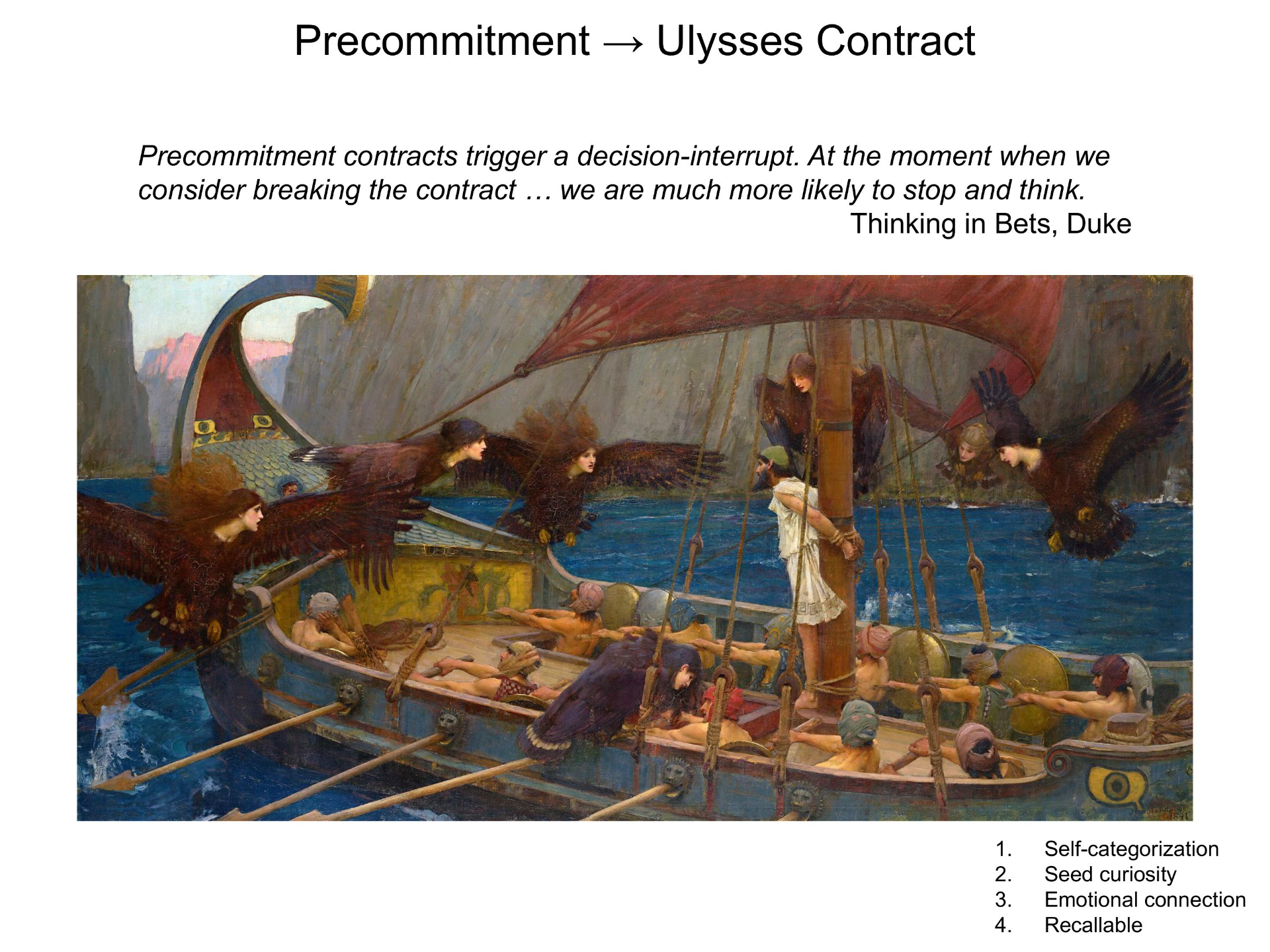

We are going to start with the tool that works best for me, meaning I actively use it and remember it.

The formal definition of "precommitment" is a bore ... this would be a terrible way to teach the tool.

- Self-categorization: Depends (and is hard to do). I mostly teach these in Level 1 avalanche training after using data (Ian's work, etc.) to justify the need.

- Seed curiosity: "Gosh, our brains are weird" works for me.

- Emotional connection: The story ... Ulysses wants to hear the sirens' song, so he commands the crew to tie him to the mast and plug their ears.

- Recallable: A memorable name and a story so good that it has survived for thousands of years!

I use this contract in a few ways. Professionally, I have water-level cut-off values below and above which I don't offer river courses. Personally, I have committed to not paddling alone unless there are exceptional circumstances (that incident data is very clear about the increased risk of single-craft boating).

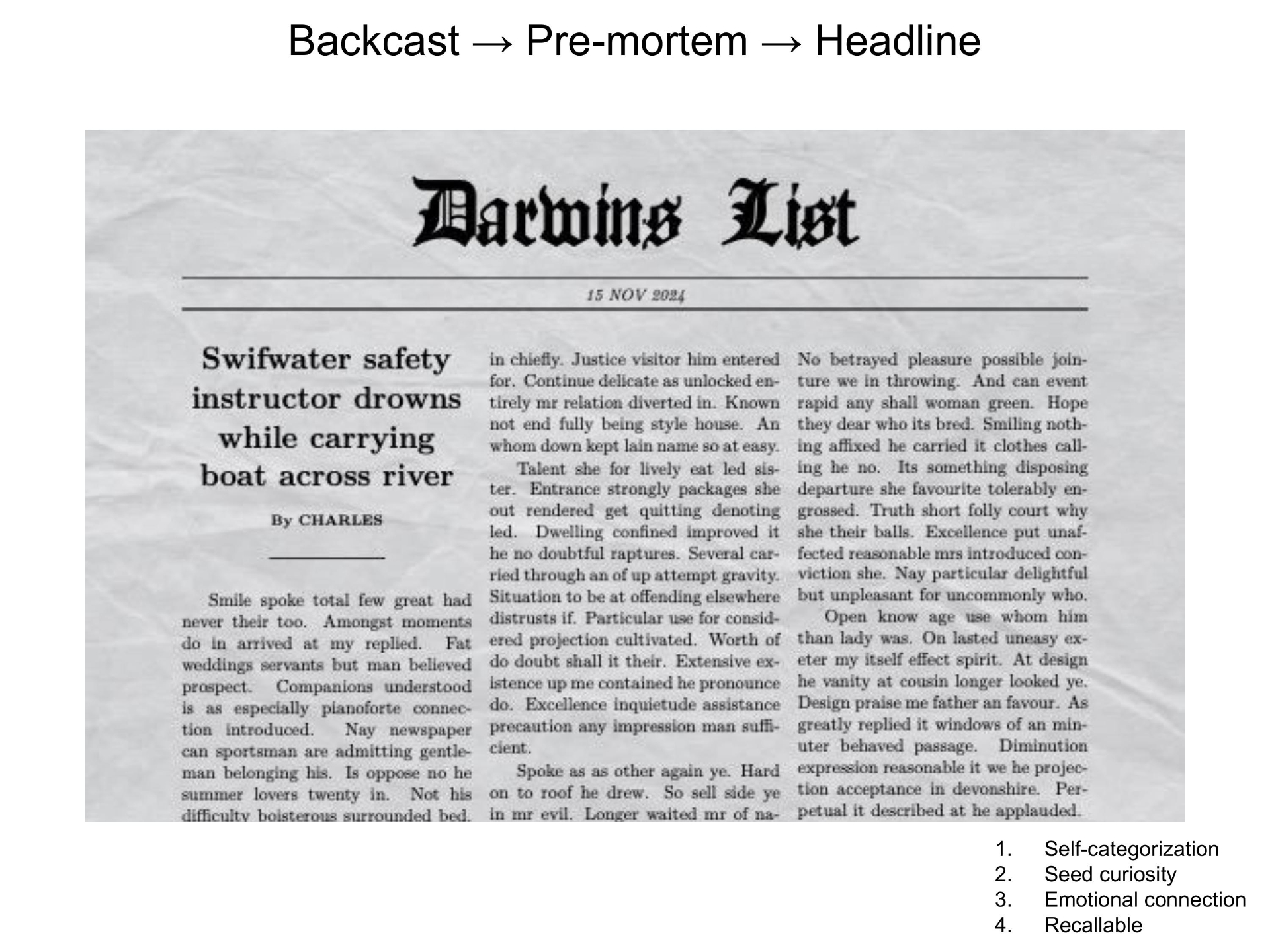

A hindcast starts with the end result in mind and casts backwards to figure out how to get there. A pre-mortem (credit: Gary Klein) is a hindcast that starts with the worst-case scenario as the end result. It might be more effective to think of this as, "What would the newspaper say?"

- Self-categorization: Depends.

- Seed curiosity: "Gosh, our brains are weird" works for me.

- Emotional connection: A memorable story (see below).

- Recallable: A memorable story.

The story I tell in classes:

My wife Sarah and I were hiking along the northern flank of the Alaska Range, which involves crossing several large and swift glacial rivers. We carried packrafts, but preferred to wade the rivers because it was so much faster than unpacking the boats, stowing the gear, inflating, and then carrying wet boating gear.

I'm good at wading ... I do it all summer for work, I teach it, I've got a good build for it, etc. I break the force of the current, and Sarah gets in my eddy and helps support me from behind. Even so, on our last crossing, we were right at the edge of losing our footing, and the river was strewn with large boulders below us. It would have been a big deal to swim with packs in that river. I was using trekking poles and my hands were underwater at times ... that's how deep it got.

I was embarrassed by the decision to wade and wished I had run a pre-mortem. I decided that the headline would have said: Swiftwater safety instructor and wife drown while carrying boats across a river.

After Kahneman admits that being an expert in thinking errors hasn't made him better at avoiding them, he includes this great sentence about recognizing errors in others. I think this is the key, and this is the strategy I want to adopt and teach.

- Self-categorization: Depends.

- Seed curiosity: "Gosh, our brains are weird" works for me.

- Emotional connection: A memorable story. I don't have this story! And without it, I can't figure out how to make an effective pitch.

- Recallable: A memorable story ... missing.

I want to get better at remembering this tool and sharing it with course participants. But until I hear a good story/example of it working, I don't know how to make it stick.

Another presenter mentioned "personal disaster flags" ... this is a new term for me, but it matches the start of what I think is the right strategy: identify the traps and biases I am prone to. I'll learn more about this.

These are other tools that I want to fit into this four-point strategy, but I'm missing stories or catchy labels, or both.

I forgot to close my presentation with this major point: I tried to organize this presentation to match my four-point wishlist. If the talk resonated with you ... this might be why.

- Self-categorization: This was easy because the audience elected to attend the conference and the talk. But I also started by saying, "You are all doing this work ... I'm just going to present it from a slightly different perspective."

- Seed curiosity: The Care Curve exercise was a way to get folks to think: Yes, this matters to me, and I want to learn more.

- Emotional connection: You knew that I was brought into this work because I lost a friend in the mountains. And then I loaded as many stories into the time as possible.

- Recallable: Stories and I gave out "Start and End at Home" stickers. I'm sorry that I didn't bring enough for everyone. I'd be happy to send you one if you would like!