Risk Management for Field Scientists

NAU workshop, October, 2023. This page is not meant to be self-explanatory.

Jump to:

Objective hazards: Environmental

Digital mapping

Near-real-time satellite imagery

Weather and sensor resources

Toolbox: Managing objective hazards

Decision-making

Toolbox: Making better decisions

Group management

Toolbox: Group management and communication

From the environmental perspective:

-

Hazard: Objective, things we can’t control (landslide, earthquake)

-

Exposure: People/property that can be harmed

- Likelihood of harm = Vulnerability. How harmful? How likely? We have some influence over these, e.g., building codes, airbags. This is the human part.

From the work/play perspective:

- Hazard

- Objective: The things we can’t control

- Subjective: Human factors such as decision-making and lack of training.

- Exposure

- The potential for severe injury; degree. E.g., height.

- 'Likelihood of harm' is wrapped up in the subjective hazards and exposure.

I prefer the environmental framework and will use it during our time together: Hazard, exposure, vulnerability

An example of adjusting the dials:

- Hazard: Bee sting, anaphylaxis

- Exposure: Sarah

- Vulnerability:

- In the backyard? Not too bad. Ambulance, hospital, etc.

- In the Alaska Range? Extreme.

[Exercise blocks]

Partner up to discuss the prompt and then (optionally) share with the group.

Note: Talking about risk and hazard can be activating for folks with stress injuries. Take care of your needs.

When have you felt at risk? Evaluate the experience in terms of hazard, exposure, and vulnerability.

In the simple risk assessment framework of “What can go wrong?” ...

Vulnerability offers: “What are we going to do about it?”

- Training

- Planning

- Equipment

Vulnerability is where we have the greatest influence, so let's use it.

List three environmental hazards that you might encounter in your work or play.

For each hazard:

- What is exposed?

- How can you reduce your vulnerability?

Exposure and vulnerability give us some control over the probability and consequence of something going wrong.

Environmental

- Probability: We have no control.

- Consequence: We have some control (building codes, life vests).

Human

- Probability: We have some control (go, don't go).

- Consequence: We have some control (training, communication).

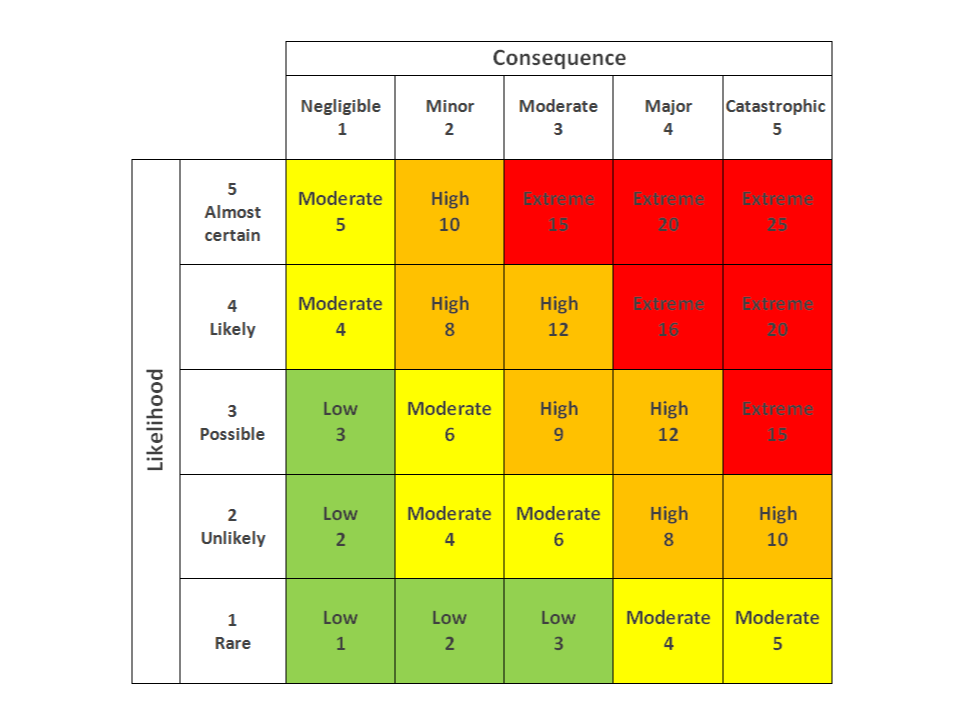

Assessment matrices

An assessment matrix can help us recognize unacceptable risks and leverage control to mitigate them.

A simple (qualitative) matrix: Professional climber Will Gadd uses these degrees of consequence with his kids:

- Bumps and bruises

- Hospital

- Death

A quantitative matrix:

Pros:

- Forces us to evaluate the probability and consequence of a hazard.

- Quantification can streamline decision-making.

- Decisions are easy in the green and red corners.

Cons:

- Quantifying likelihood and consequence is ripe for bias! (We'll talk about bias soon.)

- Number values lose meaning: 'Moderate' in the upper left and lower right are very different!

Maybe we are better off with something in between?

Plot the hazards from your previous list in likelihood/consequence space.

Action items

It is useful to match the assessment matrix with action items. Here is an example from Stanford's Laboratory Risk Assessment Tool.

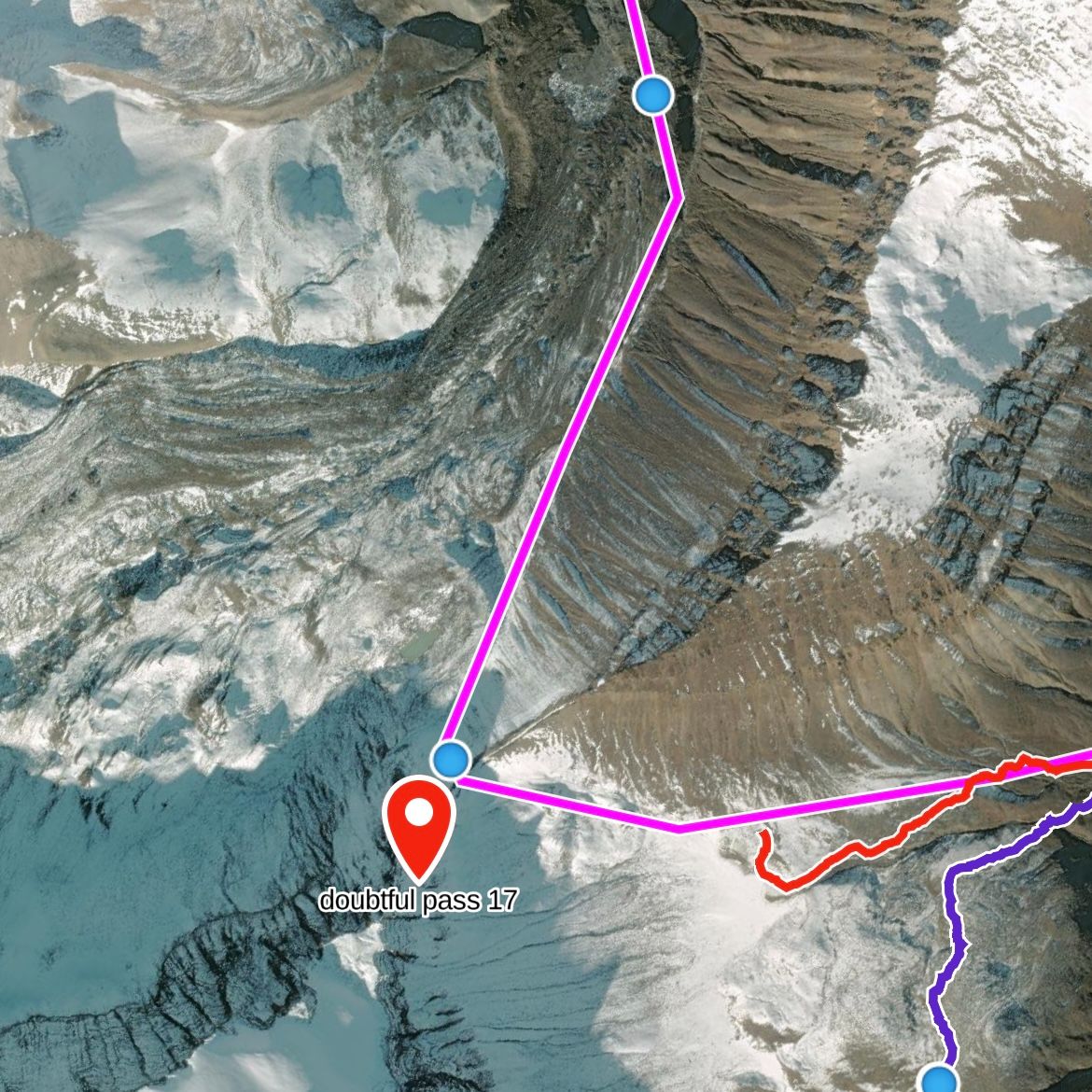

Google Earth Pro (Desktop)

- Best for exploring the landscape in 3D on a big screen.

- Good feature and file management.

- Import CalTopo’s layers to create a real powerhouse (requires a CalTopo subscription).

Weaknesses: Outdated design, steep learning curve, basic route-planning tools, and requires importing and exporting files for use in navigation applications.

CalTopo

- Best one-stop-shop for advanced route planning and navigation.

- Easy route sharing.

- Includes advanced tools such as splitting and joining line segments, adding mile markers, etc.

- Best map printing capabilities.

- Familiar to SAR teams.

Weaknesses: Outdated design and less intuitive to new users. No 3D capabilities.

Gaia GPS

- Best one-stop-shop for general applications.

- Polished interface.

- Huge selection of basemaps and layers.

- Most mature phone app.

Weaknesses: Lacks some of the advanced route planning features available in CalTopo. Complex route drawing is cumbersome. Feature management (waypoint, route, area) is overly complicated.

Toolbox: Managing objective hazards

Awareness

- Shared common vocabulary for risk assessment

Risk assessment

Formalize the use of an assessment framework:

- Adjust hazard, exposure, and vulnerability to match the situation

- Use an assessment matrix and action items

Planning and preparation

- Digital mapping

- Satellite imagery

- Weather and sensor data

Examples of subjective hazards:

- Thinking errors

- Inadequate training and experience

- Preparedness and ability to respond

- Decisions

- Group morale

- Physical conditioning and overexertion

- Time management

- Complacency

- Campsite selection

- River crossing location

Let's clump these into three categories:

- Decision-making

- Group management

- Communication

Goals

All three of these subjective hazard categories are highly dependent on our goals.

We get in trouble when our goals exceed our capabilities AND we are in an environment where consequences are high.

In addition to:

- "What can go wrong?"

- "What are we going to do about it?"

We need to ask:

- "Is it worth it?"

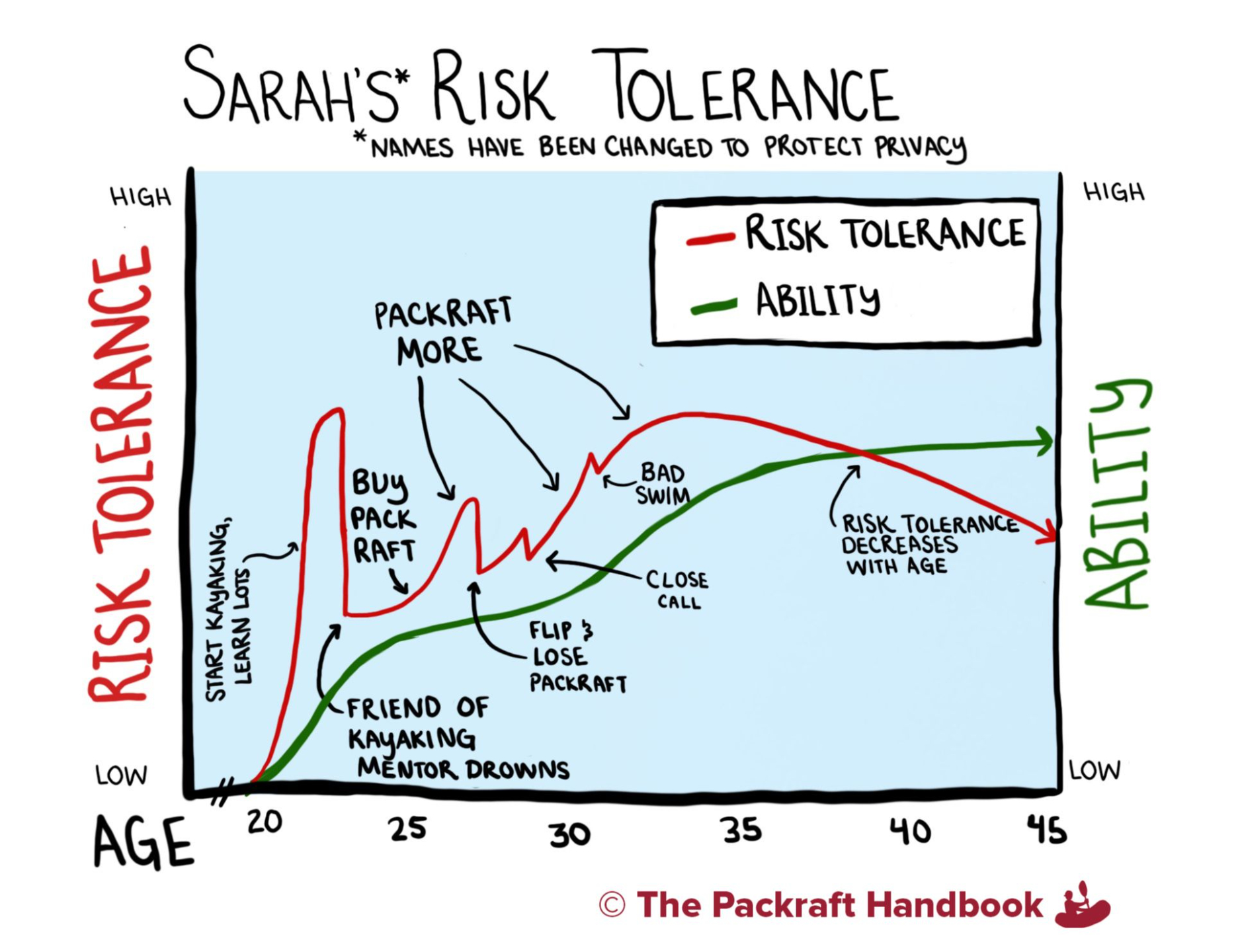

Risk tolerance

Our willingness to expose ourselves to a hazard is a function of risk tolerance: the willingness to accept that something might go wrong. Risk tolerance changes throughout our lives.

Plot your risk tolerance as a function of age or other major life events.

Decision-making

We make decisions based on our experience, but experience isn't a reliable educator.

- We learn more when we are wrong; we need feedback. E.g., A/B quiz example.

- Wicked learning environments

- Complexity and biases

Heuristic traps

Heuristics are mental shortcuts. Heuristic traps are shortcuts that increase our exposure and vulnerability.

Here's how avalanche educators try to increase awareness of heuristic traps:

Also: Confirmation bias, e.g., social media. Here's an exhaustive list.

Recall decision-making mistakes that you were involved with. Were any heuristic traps involved?

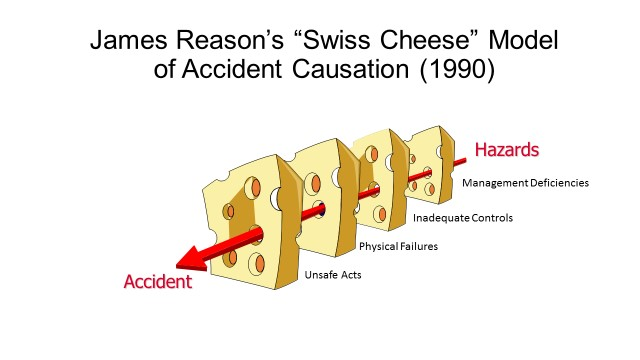

Incidents are rarely due to one bad decision

A better model is that the holes in our defenses happen to align perfectly wrong: A rush to get out the door, wrong shoes, rainstorm, sunset.

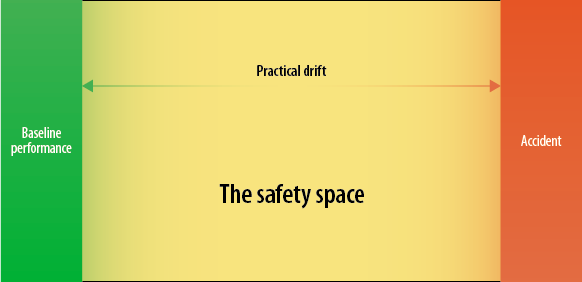

Safety drift

We tend to drift within the safety space.

- "Culture of safety" efforts drift toward the baseline.

- Complacency drifts toward incidents.

- Major incidents cause a rapid/rigid swing back to the baseline.

- Gradual changes in norms or routines are particularly troublesome.

- Where is the next decision point?

- Does the next leg have today's avalanche problem?

- What is our travel plan?

- Is there anything that we missed?

Awareness

Practice thinking about heuristics to make them less abstract.

- Include heuristics in self- and team-assessments.

- Trust gut instincts and emotions. ("Subjective!")

Zoom out: “What is missing? What is irrelevant?”

Use these prompts to test for biases.

- E.g., Flipping heads 10 times in a row; 1 in 100 odds of losing everything

Anchoring

Identify the baseline.

- What’s the right thing to do?

- Set the anchor, then justify movement from it.

Checklists

Any/all complex tasks (simple vs. complicated vs. complex)

Recall the decision-making mistakes from the previous exercise and apply these tools to mitigate them.

Group management

Working with others involves managing different risk assessments and tolerances.

We can foster a healthy group dynamic by trying to reduce stress and increase communication.

Stress

Stress limits our performance, our awareness of safety drift, and our ability to react when things go wrong.

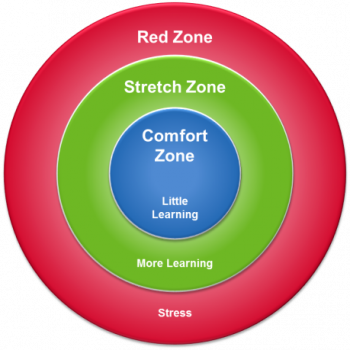

Comfort zones

- Anticipate your own stress level and that of the participants.

- You might be in your comfort zone but others/students are not.

- +1 / 0 / -1 self-assessment. Is the team in the positive?

Make a +1 / 0 / -1 self-assessment for a potential outing.

Working with a small comfort zone:

- Reduce exposure to stressors/activators

- Reinforce the support system

- Orient to the available resources

- Buddy-up

- Titration

- Pendulation

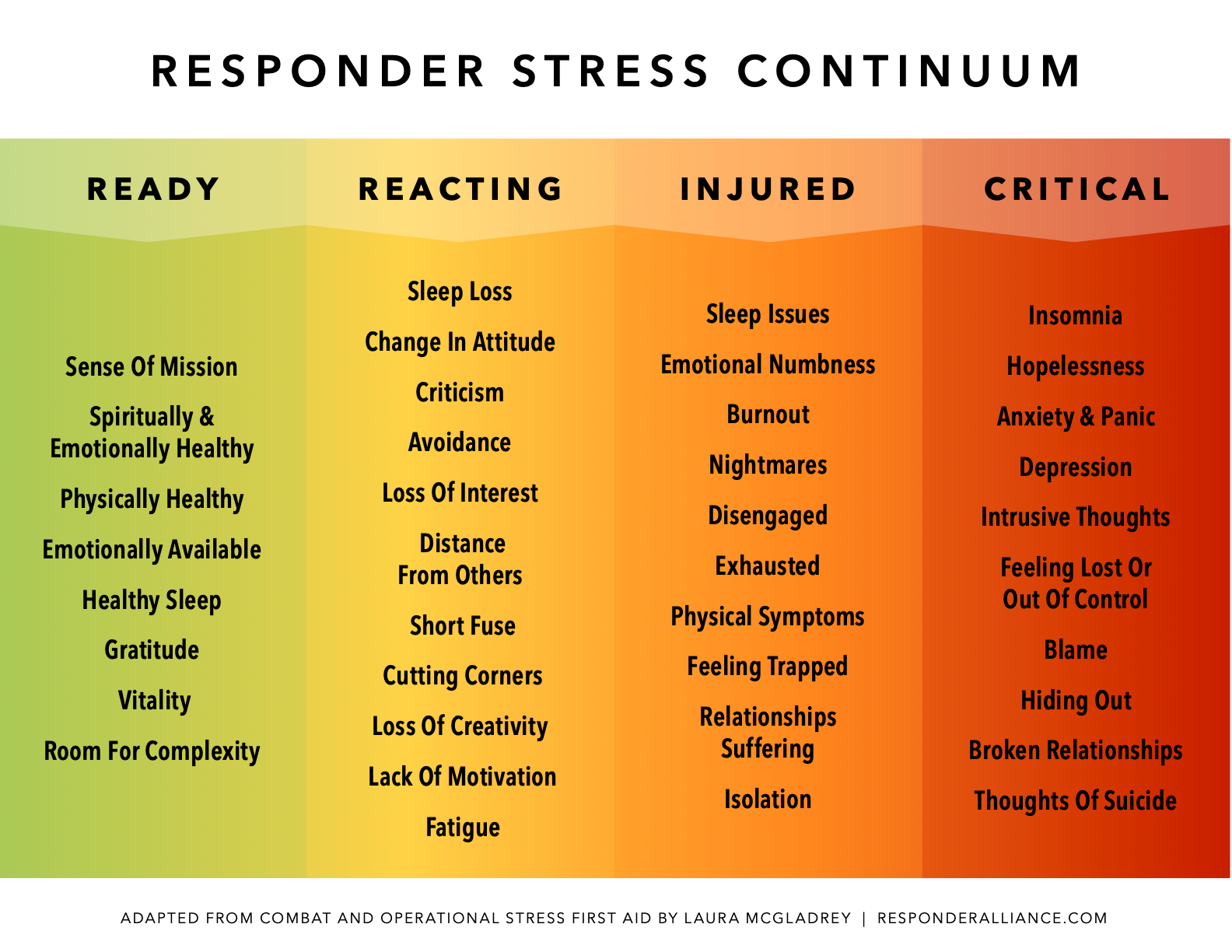

The stress continuum

"A color-coded 'How are you doing?' scale."

- Evaluate self/team condition

- Recognize your ability to react if something goes wrong

Apply the comfort zone circles or stress continuum to a time you experienced or witnessed a stress injury.

Communication

Ultimately, the thing that goes wrong is communication.

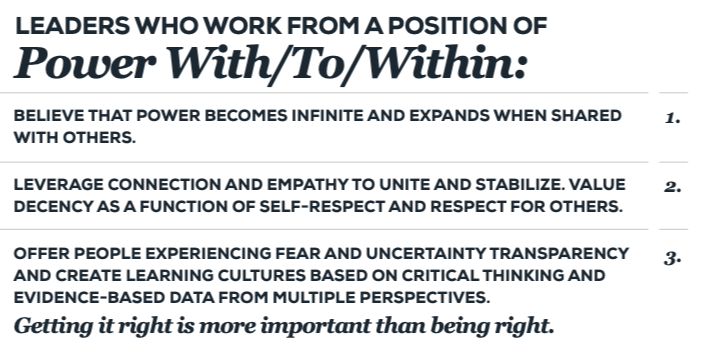

Power and leadership

Complex tasks require specialization.

Success requires open communication between specialists—teamwork!

-

Set the tone early

-

Role model best behavior

-

Establish the power structure: We are a team.

-

Empower: Anyone can say stop.

-

Earn trust: Learn names, show that you care.

- Calling in vs. calling out

Listening

- Foster an environment where questions are welcome

- Be a good listener and check for understanding

- Read body language, silence. If in doubt, ask 1-on-1 out of earshot of others.

Asking

- Ask generic questions of the group.

- E.g., “What could go wrong here?” Instead of, "Are you feeling okay with this?"

Debriefing

The learning process is incomplete without reflection and assessment.

- Reflect and take notes

- Involve mentors and experts.

Practice setting the tone with a pre-brief:

- Objectives: "We are here to learn. We don’t learn well when we are scared or too tired, so let’s keep checking in with each other about our energy levels."

- Risk: "Here’s what is most likely to go wrong ..."

- Mitigation: "Here’s what we will do if that happens ..."

- Need-to-knows: Med kit, communication plan, etc.

Leadership

A few final thoughts ...

- Ideally, leaders can work on autopilot to then focus on others’ conditions, environmental hazards, etc.

- Anticipate foreseeable events and what-ifs.

- Have a Plan B.

- Plan for emergencies.

- Have the technical skills to respond (medical training, etc.).

Toolbox: Group management and communication

Stress awareness

Recognize and incorporate a stress assessment:

- Comfort zones

- +1 / 0 / -1 self-assessment

- Stress continuum

Goals and expectations

- Vocalize goals: Short-term, attainable, realistic

- Be clear about expectations

Communication

- Set the tone: Foster an environment of teamwork and open communication

- Call in: Let's solve this thing together

- Collect feedback, reflect, assess

Leadership

- Train and prepare so that you can be on autopilot as much as possible, allowing you to focus on the group and environment.

- Anticipate foreseeable events, what-ifs, and emergencies.

Synthesis

Take some time to create a list of the most likely environmental and subjective hazards you might encounter. A partial list of considerations is provided in the risk management document linked below.

For each hazard, come up with a 'What are we going to do about it?' plan.

The risk management document also includes an example emergency plan, trip description, and post-trip report. Copy and customize these sections to meet your needs.

View the risk management documentNot covered:

- The legal aspect of risk management and emergencies: Liability.

Further reading:

Ajango, Deb (2005). Lessons Learned II.

Gawande, A. (2011). The Checklist Manifesto.

Kahneman, D. (2013). Thinking, Fast and Slow.

Soyer, E. and Hogarth, R. (2020). The Myth of Experience.